Yves GARY Hits: 5166

Category: ARROW

By William P. Stephens - MotorBoating oct. 1944

By William P. Stephens - MotorBoating oct. 1944

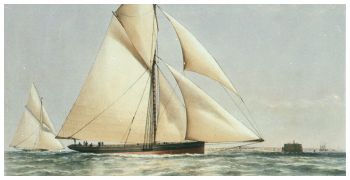

CONTEMPORARY with Pearl, and even more famous in racing, was the cutter Arrow, built in 1822. Her first owner, Joseph Weld, was, like the Marquis of Angelsey, one of the founders of the Royal Yacht Squadron; like the Marquis, he had ideas of his own, and he chose as a builder, Inman of Lymington, to carry them out.

He is said to have based his model on a fast smuggler, and, like Pearl, she was of lapstrake construction, about 70 feet in length and of 85 tons. She proved successful from the start; in 1825 she sailed a match with Pearl for 500 pounds. In accepting Mr. Weld's challenge the owner of Pearl is said to have remarked: "If the Pearl should be beaten I will burn her as soon as we get back.” However, she won and the cremation was postponed.

Mr. Weld sold Arrow in 1823 and continued his experiments with Lulworth in that year, Alarm in 1830, Meteor in 1856 and a second Lulworth in 1857. After passing through the bands of two other owners Arrow was sold to be broken up in 1845: it is probable that the lightly built lapstrake hull had been strained by continuous hard racing.

How she started a new career is told by Thomas Chamberlayne, another member of the Squadron.

"I bought the Arrow when she was lying on the hanks of the river Itchen, full of mud and water and waiting to be broken up for firewood; it was December 1846 and I gave 116 pounds for her. Her length was then 61 feet 9½ inches; breadth, 18 feet 5¼ inches; and depth of hold 8 feet 8 inches.

My wish was to get her midship section to build from, knowing how celebrated she had been in her former days. I built from the old moulds, and, out of respect for my esteemed friend, Mr. Weld, her original constructor, called her after the old vessel, "The Arrow." I have since altered her on several occasions, bringing her up to 84 tons, then to 117."

Such men as Angelsey, Weld and Chamberlayne were not out for bargains by building in one-design classes and thus saving the designer's fee, they spent their money freely in backing the builder which each chose as the best to realize his ideas: many of their experiments were costly failures, yet all served to further the improvement of yachts.

The sentiment of the day, 1874, in matters both technical and ethical, are shown in a later letter in answer to a request by Dixon Kemp for the lines in order to compare them with other yachts.

As the result of this "generous concession" the lines were taken off by Mr. Kemp and a copy given to the owner; but, when in 1875, Mr. Kemp asked permission to publish the lines in The Field, he was again rebuffed as follows:

It will be noticed that in this example of fine old crusted conservatism the writer always speaks of his yacht as a "vessel," and that he uses the definite article before the name.  As to the "act of kindness" to the "public builders," many at that date shared his idea; as to the sanctity of the lines of their yachts.

As to the "act of kindness" to the "public builders," many at that date shared his idea; as to the sanctity of the lines of their yachts.

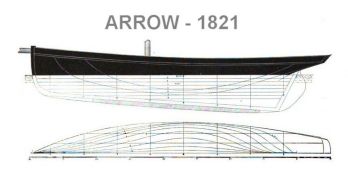

It was not until after Mr. Chamberlayne's death that his son permitted the lines as here shown to be published in The Field, March 1879, her dimensions then being: l.o.a., 90 feet 2 inches; l.w.l., 79 feet 2 inches; breadth, 18 feet 4 inches; depth, 8 feet 2 inches; draft, 11 feet 6 inches; displacement, 106 tons; ballast, 40 tons (on keel, 13.7 tons) ; area of lower sails, 4,680 square feet. By this time she had been repeatedly rebuilt, the length for tonnage had grown from the original 61.75 to 81.4, showing a lengthening of 20 feet; in fact, nothing was left of the original Arrow but her midship section. At this date, which ended her racing career of 53 years, she was described among a fleet of more modern yachts as being “the most formidable cutter afloat."