Yves GARY Hits: 6186

Category: 1870 : CHALLENGE N°1

A long wait

A long waitEighteen years were destined to pass between the winning of the cup by the America and the first challenge for it. The reasons for this lapse of time without a contest for the trophy may be easily discerned. English yachtsmen were digesting the food for thought the America had given them and profiting by the lesson, while during five years of war beginning with 1860, the United States had other things to think about than yachting.

The revival of the sport in this country was brilliant, and attracted the attention of the world. As the Yankees were the first to send a yacht across the Atlantic ocean, they were the first also to arrange an ocean race between yachts. Such a race was sailed in the winter of 1866, between the schooners Henrietta, owned by James Gordon Bennett, Commodore of the New York Yacht Club, the Fleetwing, owned by George and Franklin Osgood, and the Vesta, owned by Pierre Lorillard. This race is worthy of mention in connection with the America's cup because of its effect in England. Interest in American yachting, which had been crushed by the war, was revived by the race of these three clipper vessels.

Sappho was in cruising rig, and had on board several tons of stone ballast she had carried across the ocean. She was not, therefore, at her best. Her performance, however, was a blessing in disguise to the sport of international racing, for it gave Mr. Ashbury the idea that he could easily defeat any American yacht, since this was the clipper of them all.

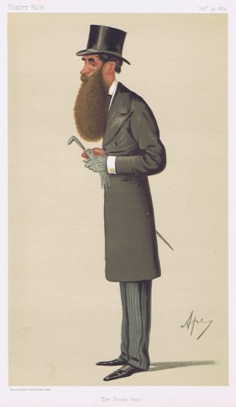

He therefore addressed a communication to the New York Yacht Club, October 3d, 1868, that was broad enough to show him to be, in his aspirations at least, considerable of a sportsman. While his communication was tentative rather than definite, it had the effect of a specific challenge.

The New York Yacht Club did not accept Mr. Ashbury's invitation to participate in ocean races, but took up with his otter to sail for the America's cup, informing him that it "could only take cognizance of and respond to that portion of said communication having reference to the challenge cup won by the America," and calling his attention to the condition that a challenge for it must come through a regularly organized foreign yacht club.

Mr. Ashbury responded, February 24th, 1869, that he would obtain consent from "one of the several Royal Yacht Clubs" to which he belonged, to sail Cambria as its champion vessel. On July 20th, 1869, he wrote that he hoped to sail under the colors of the Royal Thames Club, to which he would present the cup, if he won it, "to be held as a challenge cup, open to any royal or other first-class recognized yacht club to compete for; providing six months notice is given, and the course not less than 300 miles in the channel or any other ocean." In case all the conditions he named were approved Mr. Ashbury stated he was ready to sail for this country about August 27th.

Mr. Ashbury responded, February 24th, 1869, that he would obtain consent from "one of the several Royal Yacht Clubs" to which he belonged, to sail Cambria as its champion vessel. On July 20th, 1869, he wrote that he hoped to sail under the colors of the Royal Thames Club, to which he would present the cup, if he won it, "to be held as a challenge cup, open to any royal or other first-class recognized yacht club to compete for; providing six months notice is given, and the course not less than 300 miles in the channel or any other ocean." In case all the conditions he named were approved Mr. Ashbury stated he was ready to sail for this country about August 27th.

The New York Yacht Club did not relish Mr. Ashbury's attempt to set aside the deed of gift, and make new conditions under which the cup should be sailed for, should he win it. Neither did it accept the condition that it should defend the cup with one vessel only. There is no record to show that it told Mr. Ashbury this in so many words, or at all, until he had cabled: " Will the Cambria be allowed to sail your champion schooner for the America's cup on basis of my letter of July 20th '? "

To this Mr. Ashbury received a reply not distinguished for its directness, though it conveyed the club's meaning that if Mr. Ashbury wished to sail for the America's cup he would have to sail against a fleet. The America had not sailed against a fleet, but as one of fifteen vessels, each trying for the cup. In this case it would be a fleet against one vessel. There was none of the gospel injunction, "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you," in this position. Conditions construed as unfair by Commodore Stevens were to be meted out in fact to the first challenger who appeared. Viewed in the light of sporting ethics of to-day, it appears that Mr. Ashbury had the broader view of the subject. The cup had ceased to be a squadron trophy, to go to the individual who won it, when it passed into the hands of the owners of the America. It had been given in trust into the keeping of the New York Yacht Club, to be sailed for as an international challenge cup, in races between clubs representing their respective nations.

The assumption of Mr. Ashbury that it should be sailed for vessel against vessel, and not by a single vessel against a fleet, was sound and right, as later experience showed; for before the cup was sailed for a second time on this side of the water the New York Yacht Club was forced to recede from the position it took in the following note to Mr. Ashbury, in response to his cable quoted above:  "The necessary preliminaries having been complied with by you upon your arrival here, you have the right, provided no match can be agreed upon, to sail over the annual regatta course of the New York Yacht Club." Mr. Ashbury was assured he would be “heartily welcomed," and that he would find the club prepared to "maintain their claim according to the conditions upon which they accepted the cup." It will appear later that the club could not uphold the view that one of these conditions was that a challenger should sail against a fleet with a single vessel.

"The necessary preliminaries having been complied with by you upon your arrival here, you have the right, provided no match can be agreed upon, to sail over the annual regatta course of the New York Yacht Club." Mr. Ashbury was assured he would be “heartily welcomed," and that he would find the club prepared to "maintain their claim according to the conditions upon which they accepted the cup." It will appear later that the club could not uphold the view that one of these conditions was that a challenger should sail against a fleet with a single vessel.

Nothing came of Mr. Ashbury's challenge, as he regretted he could not race that season, his reason being that he could not contest for the cup on the basis of his challenge.

It will be observed that in this, the first correspondence looking to a race for the cup as a challenge trophy, both parties fell into error; the New York Yacht Club in its lack of sportsmanlike spirit as shown by its interpretation of the deed of gift, and Mr. Ashbury in attempting to dictate terms. Both sides were feeling their way, according to their lights, and the time was not ripe for the broad and satisfactory contests for the cup that were to come in after years.

Mr. Ashbury, with a tenacity worthy of the cause, returned to the business of challenging for the cup in November of 1869. He had arranged an ocean race with Dauntless, James Gordon Bennett owner, to be sailed in September, 1869, but the arrangements fell through, as Dauntless could not be got ready on time. On November 14th, 1869, Mr. Ashbury wrote the New York Yacht Club that in the event of his racing Dauntless across the ocean in March, 1870, he would sail for the cup on May 16th, 1870, over a triangular course "from Staten Island, forty miles out to sea and back." Just how he expected to lay a triangular course from Staten Island out to sea and back he did not explain. His letter also contained these lines, which, in view of his contention that conditions which prevailed in the race of 1851 no longer held good — which diey did not — appears somewhat sophistical:

Mr. Ashbury, with a tenacity worthy of the cause, returned to the business of challenging for the cup in November of 1869. He had arranged an ocean race with Dauntless, James Gordon Bennett owner, to be sailed in September, 1869, but the arrangements fell through, as Dauntless could not be got ready on time. On November 14th, 1869, Mr. Ashbury wrote the New York Yacht Club that in the event of his racing Dauntless across the ocean in March, 1870, he would sail for the cup on May 16th, 1870, over a triangular course "from Staten Island, forty miles out to sea and back." Just how he expected to lay a triangular course from Staten Island out to sea and back he did not explain. His letter also contained these lines, which, in view of his contention that conditions which prevailed in the race of 1851 no longer held good — which diey did not — appears somewhat sophistical:

"The cup having been won at Cowes, under the rules of the R.Y.S., it thereby follows that no centre-board vessel can compete against the Cambria in this particular race."

To this argument the New York Yacht Club replied that it had no power to deviate from the terms of the deed of gift, and called attention to the condition that "in case of disagreement " the match is "to be sailed according to the rules and sailing regulations of the club in possession". The club stated that it could not therefore entertain a proposal to exclude from the race any yacht duly qualified to sail under the rules and regulations of the New York Yacht Club.

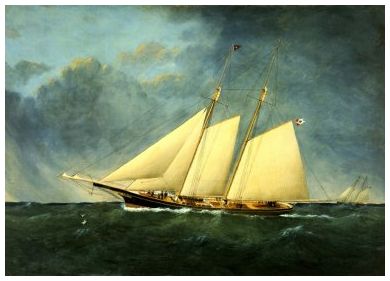

Notwithstanding his dissatisfaction with the terms offered, Mr. Ashbury came to this country with his schooner. He had sailed Cambria in three races against Sappho before leaving England, and lost two, defaulting one, because the course to Cherbourg and back did not on the day set afford a race to windward and leeward as agreed. Sappho the year before had been "hipped" (made wider amidships) by Capt. "Bob" Fish of Bayonne, N. J., and was then sailing very fast, entirely outclassing Cambria.

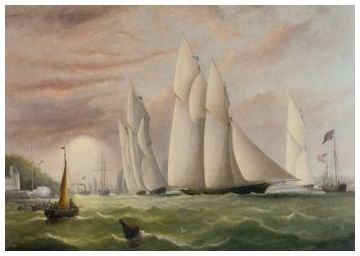

To add to the interest of the arrival of the first challenger in this country, Cambria sailed an ocean race against Dauntless from Daunt's Rock to Sandy Hook, starting July 4th, 1870. Dauntless was a fast keel schooner, 123 feet 10 inches overall, 26 feet 7 inches beam, and 12 feet 6 inches draft. She was manned for the race with Cambria by a crack crew. Her sailing-master was Martin Lyons, a smart Sandy Hook pilot, with whom was associated Capt. Samuel Samuels, a noted blue-water skipper, and “Old Dick" Brown of America fame. Some friends of the owner also sailed on the vessel. Cambria, though the slower sailer, won the race, sailing 2917 miles in 23 days 5 hours and 17 minutes, by the narrow margin of 1 hour and 43 minutes. She came by the northern course. Dauntless came by the middle course, and sailed 2963 miles, or 46 miles more than the Cambria, in 23 days and 7 hours. Her sailing-master, speaking of this race in 1901, said “there was too much amateur talent aboard."