Yves GARY Hits: 10800

Category: 1885 : CHALLENGE N°5

Evolution of yacht design

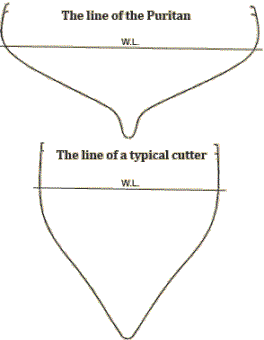

Evolution of yacht designWith the application of naval architecture to yacht design, there was a tendency to break away somewhat from hide-bound tradition in yacht building, and the claims of the English type of deep, narrow cutter were beginning to be heeded and its good points to be taken into consideration.

About the middle of the seventies one or two small cutters had been built in America, though with some modifications of the English type. These were chiefly in respect to having more beam, the beam of the English boats being unduly narrow to give them a favorable rating under their measurement rule. One or two outand-out cutters were built, with the cutter rig of housing bowsprit, loose-footed mainsail, double head rig, etc., but most of them were a compromise between the American centerboard sloop and the narrow English type.

About the middle of the seventies one or two small cutters had been built in America, though with some modifications of the English type. These were chiefly in respect to having more beam, the beam of the English boats being unduly narrow to give them a favorable rating under their measurement rule. One or two outand-out cutters were built, with the cutter rig of housing bowsprit, loose-footed mainsail, double head rig, etc., but most of them were a compromise between the American centerboard sloop and the narrow English type.

It is perhaps interesting here to begin by defining the differences between a sloop and a cutter.  These two types are not found in most modern monohulls because they were completely fused, but originally, the differences were well marked.

These two types are not found in most modern monohulls because they were completely fused, but originally, the differences were well marked.

The cutter was a deep and narrow boat with a keel, a short mast and a long topmast. She had a reefing bowsprit, to facilitate changes of sails and reefing lines, and sets her jib flying, that is on its own luif. The mainsail loose footed was not laced to the boom.

The sloop was large with small draft and have a centerboard. She had a standing bowsprit and hoists her jib on a jib stay. Her mainmast was more long and her mainsail was laced to the boom.

Then, in 1881, a little Scotch cutter called the Madge was shipped to this country by her owner, a Mr. Coats, of Scotland, on the deck of a steamer. She was 46 feet long over all, had a beam of only 7 feet 9 inches, and drew nearly 8 feet of water.

She was a regular “knife blade” or “plank-on-edge” cutter of the extreme type. This little boat was so uniformly successful in her races against American sloops of her size that she converted many yachtsmen to the type and the yachting world was for a time divided into two camps — the “cutter cranks”, as they were called, on one side, and the adherents of the centerboard sloop on the other. From this controversy a new type of centerboard sloop was evolved, combining some of the elements of each type and being a much more wholesome, abler type of craft than the old “skimming dish” single-stickers, that were said to sail on a heavy dew.

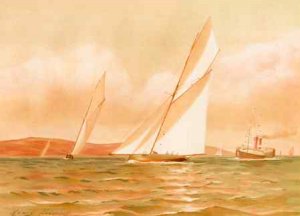

Reports from England of Genesta's success abroad in 1884, her first year, where she was conceded to be the best all-round boat, convinced the officers of the club that vigorous steps had to be taken to get a suitable boat with which to defend, none of the existing ones being considered fast enough, or large enough. So the flag officers, James Gordon Bennett and William P. Douglas, decided to build a sloop and, naturally, turned to A. Gary Smith, then the most prominent yacht designer in this country, for her design. He had turned out the last successful Cup defender Mischief, and many other fast boats. The centerboard type was decided on, though the new boat was to be much deeper than the prevailing centerboarders of the time, being a “compromise sloop”, and she was built entirely of iron, by Harlan and Hollingsworth, of Wilmington, Del. This boat was named Priscilla, and great things were expected of her when she appeared in New York waters in the early summer.

Reports from England of Genesta's success abroad in 1884, her first year, where she was conceded to be the best all-round boat, convinced the officers of the club that vigorous steps had to be taken to get a suitable boat with which to defend, none of the existing ones being considered fast enough, or large enough. So the flag officers, James Gordon Bennett and William P. Douglas, decided to build a sloop and, naturally, turned to A. Gary Smith, then the most prominent yacht designer in this country, for her design. He had turned out the last successful Cup defender Mischief, and many other fast boats. The centerboard type was decided on, though the new boat was to be much deeper than the prevailing centerboarders of the time, being a “compromise sloop”, and she was built entirely of iron, by Harlan and Hollingsworth, of Wilmington, Del. This boat was named Priscilla, and great things were expected of her when she appeared in New York waters in the early summer.

At this time the waters of Massachusetts Bay had become a great yachting center and had bred some of the finest yachtsmen on the Atlantic coast, though as a rule they were small boat sailors rather than owners of large yachts. There was a strong patriotic sentiment there that Boston and its leading yacht club, the Eastern, located at Marblehead, should be represented in an international event of this kind, and a syndicate was formed, of whom the leading members were General Charles J. Paine and J. Malcolm Forbes, to build a boat to try for the honor of defending the Cup. General Paine was also a member of the New York Yacht Club, the owner of the schooner Halcyon, and a keen, practical yachtsman.

At this time the waters of Massachusetts Bay had become a great yachting center and had bred some of the finest yachtsmen on the Atlantic coast, though as a rule they were small boat sailors rather than owners of large yachts. There was a strong patriotic sentiment there that Boston and its leading yacht club, the Eastern, located at Marblehead, should be represented in an international event of this kind, and a syndicate was formed, of whom the leading members were General Charles J. Paine and J. Malcolm Forbes, to build a boat to try for the honor of defending the Cup. General Paine was also a member of the New York Yacht Club, the owner of the schooner Halcyon, and a keen, practical yachtsman.

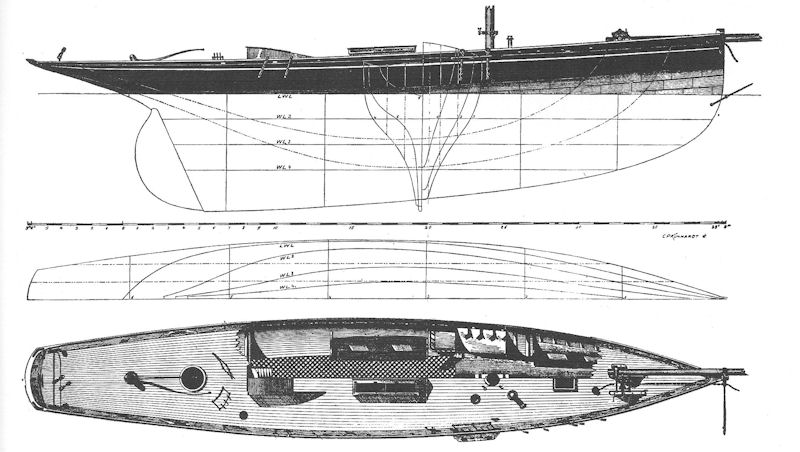

There was at that time a young naval architect in Boston, about thirty-six years of age, who had achieved considerable local reputation as a yacht designer, though he had only taken it up professionally about two years before. His name was Edward Burgess, and while his scientific knowledge was acquired as an amateur, he was clever, knew boats, and was a first-class yacht sailor. To him the syndicate went for the plans of the new yacht. It was an ambitious undertaking for a designer of his limited experience, for up to that time the largest boat he had turned out was only thirty-eight feet over all; and he was not only going up against the New York Yacht Club with its great prestige and resources, but he had to design a sloop larger than any at that time afloat in this country. But the members of the syndicate and his friends had faith in his abilities, and the result was the Puritan, launched from Lawley's yard in May, 1885, and destined to bring international fame to her designer.