Yves GARY Hits: 6743

Category: AMERICA

The America was fitted for her voyage across the Atlantic with sails belonging to the pilot-boat Mary Taylor.

The America was fitted for her voyage across the Atlantic with sails belonging to the pilot-boat Mary Taylor.

She carried forty-five tons of ballast, her racing canvas and gear were stowed in her hold, she was well provisioned, and, according to the customs of the times she carried a stock of liquor for regular consumption, and with which to drink the healths of victors and vanquished on the other side.**

On the 17th of June the America's certificate of registry was issued at the New York custom-house. It was as follows :

"Register 290, June 17th, 1851: William H. Brown, master, builder and sole owner of the yacht schooner America. Built in New York in 1851. Length 93 feet six inches, breadth 22 feet six inches, depth 9 feet, measurement 170, 50-95ths tons."

| ** The late W. T. Porter, for many years editor of the Spirit of the Times and a friend of Commodore Stevens, is the author of the following anecdote in connection with the America's voyage to England : " Before the America sailed Mr. Stevens placed on board two dozen of the celebrated Bingham wine, derived from the cellars of the late Mr. Bingham of Philadelphia, father of the wife of the late English minister to the United States, Lord Ashburton. It was more than half a century old, and the Commodore designed to drink it to the health of Her Majesty. It would appear that the Commodore's excellent wife in 'setting to rights' various little matters in relation to the outfit of the America, concealed these two dozen of Madeira in a secret cranny in the vessel, so that when he sold her, without his knowledge the wine went with her. He presumed that through some oversight it must have been taken ashore, and never discovered the mistake until his return home, when he immediately wrote Lord de Blaquiere [then owner of the America] that if he would look in a certain hidden he would find some wine ' worth double the price of her,' of course making him a present of it." |

The America was delivered to her owners next day, was ready for sea on June 20th, and sailed the next morning for Havre. She carried but six men before the mast. Capt. ' Dick" Brown, a Sandy Hook pilot, part owner of the Mary Taylor, was sailingmaster, and Nelson Comstock mate. Messrs. George Steers, James R. Steers, and young Henry Steers, the latter's son, aged 15, went as passengers, and helped on occasion to work ship or stand watch. The total ship's company, with cook and boy, numbered thirteen. Commodore Stevens, Edwin A. Stevens and George L. Schuyler purposed joining the yacht in France, but as Mr. Schuyler was prevented almost at the last moment from going, Col. Hamilton, his father-in-law, went in his place, crossing the ocean, as did the Messrs. Stevens, by steamer.

Incidents of the America's voyage across the Atlantic, which was made in 17 1/2 days, are especially interesting, as she was the first yacht to cross the ocean in either direction. The only facts concerning the voyage that have been preserved are contained in a personal journal, or log, kept by James R. Steers. This book came into the possession of James W. Steers, son of George Steers, of Brooklyn, and is still in his family.

There is a droll humor shown in parts of the log, which begins with the following entry on June 21st, 1851 :

"Left the foot of 12th Street 8 a. m. Nine o'clock took steamer and towed out of the East River. Eleven o'clock, 10 miles out, parted with our friends. One o'clock George Gibbons came on board, with officers. One o'clock and 12 minutes the steamer Pacific [one of the early Atlantic liners] passed us and gave us nine cheers and two guns, which were returned by us with as good heart as given. At 3 o'clock passed Sandy Hook bar going 11 knots. At 10 o'clock p.m. rather squeamish; Captain, second mate and carpenter took a little brandy, say about 10 drops."

Having thus conscientiously recorded the extent of his shipmates' indulgence, Mr. Steers entered into nautical data, with frequent references to the cuisine of the ship.

On June 22d he put down : "Set the square-sail, or Big Ben, the Captain calls it." On that day the vessel made 284 knots, the best 24-hours' run of the voyage. Two days later she made 276 knots in 24 hours. The log for that day reads : "Commenced with light breeze. Passed a ship with a large Cross in her fore topsail. Was not near enough to speak. Had for dinner to-day a beautiful piece of Roast Beef, and green peas, rice pudding for dessert. Everything set, and the way she passed everything we saw was enough to surprise everybody on board."

On June 22d he put down : "Set the square-sail, or Big Ben, the Captain calls it." On that day the vessel made 284 knots, the best 24-hours' run of the voyage. Two days later she made 276 knots in 24 hours. The log for that day reads : "Commenced with light breeze. Passed a ship with a large Cross in her fore topsail. Was not near enough to speak. Had for dinner to-day a beautiful piece of Roast Beef, and green peas, rice pudding for dessert. Everything set, and the way she passed everything we saw was enough to surprise everybody on board."

On June 26th they had "good winds, roast turkey, and brandy and water to top oft with," and made 254 knots. The next day, with light winds, the run was 144 knots. Mr. Steers wrote of the America on this day : "She is the best sea boat that ever went out of the Hook. The way we have passed every vessel we have seen must be witnessed to be believed."

The following day he wrote: "The Captain said that she sails like the wind. We saw the British bark Clyde of Liverpool, right ahead about 10 o'clock, and at 6 p. m. she was out of sight astern."

The record of the next two days was 150 and 152 knots respectively. The entry in the log contains this plaint : "Thick, foggy, with rain. I don't think it ever rained harder since Noah floated his ark."

But there seemed to be a solace, for the entry continues : " Had to-day fried ham and eggs, boiled corned beef, smashed potatoes, with rice pudding for dessert." The dinner may not have agreed with the writer's stomach, for this line follows : "Should I live to get home this will be my last sea trip."

The record for the next day was 129 knots. Mr. Steers wrote : "This is the first day the sun has shone, and that only half day; it will rain again before night."

The record for the next day was 129 knots. Mr. Steers wrote : "This is the first day the sun has shone, and that only half day; it will rain again before night."

Wednesday, July 2d, the record was 209 knots. The log states : "At two p. M. unbent the large jib and bent the small one. It looks like a shirt on a beanpole. Passed a clipper brig going the same way, and passed her faster than she was going ahead." Then, "our cook is not a very good caterer," sadly adds the chronicler. The fact that "there was a heavy head sea on, and the ship was making the water fly some," may have affected the writer's views.

The distance covered July 3d was 219 knots, and on July 4th 179. For three days following only 147 knots were made, owing to baffling winds. On July 8th the run was 223 knots, and on the 9th 272. This entry appears on the 8th : "Our liquor is all but gone." And on the following day it is recorded that "we had to break open one of the boxes marked 'rum' [of Commodore Stevens' private stock] , as George [Steers] had the belly-ache, and all of our own was consumed ; but we were not going to starve in a market place. So we took four bottles out, and I think that will last us."

On July 10th the log records: "Fresh breezes and squalls. Three square-rigged ships ahead of us. He [the captain] made them out about 10 a.m., and they have got everything set that they can carry, but we are picking them up fast. The scene is very exciting."

On July 10th the log records: "Fresh breezes and squalls. Three square-rigged ships ahead of us. He [the captain] made them out about 10 a.m., and they have got everything set that they can carry, but we are picking them up fast. The scene is very exciting."

Who with love of the sea in his blood cannot imagine it ? The record for that day was 250 knots, and for July 11th, 166, from midnight to 8 p.m., when Havre was reached.

After the arrival of the vessel at Havre Mr. Steers' journal deals almost exclusively with personal matters, and sightseeing, there being nothing in it of value in the way of data about the vessel.

The Stevens brothers and Col. Hamilton were in France two weeks ahead of the America, and passed most of their time while waiting for the yacht in Paris. Col. Hamilton, in his "Reminiscences," (Scribners, 1869,) throws a most interesting side-light on the sentiment with which Americans then in France looked forward to the America's approaching test against English vessels. He says :

"Such was the want of confidence of our countrymen in our success, that I was earnestly urged by Mr. William C. Rives, the American Minister, and Mr. Sears, of Boston, not to take the vessel over, as we were sure to be defeated. My friend, Mr. H. Greeley, who had been at the Exhibition in London, meeting me in Paris, was most urgent against our going. He went so far as to say :

' The eyes of the world are on you ; you will be beaten, and the country will be abused, as it has been in connection with the Exhibition.'

I replied, ' We are in for it, and must go.' He replied, 'Well, if you do go, and are beaten, you had better not return to your country.'

This awakened me to the deep and extended interest our enterprise had excited, and the responsibility we had assumed. It did not, however, induce us to hesitate. I remembered that our packet-ships had outrun theirs, and why should not this schooner, built upon the best model?"

Col. Hamilton adds: "In Paris we took means to obtain the best wines and all other luxuries to enable us to entertain our guests in the most sumptuous manner."

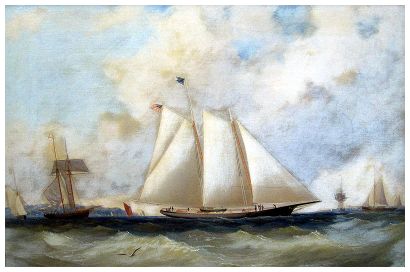

While at Havre the America was fitted out for racing in England. Her hull was here given a smart coat of black, —she wore her prime-coat of gray up to this time, —her racing sails were bent, and she was made ready in every way for the work ahead of her, though she was not put in racing trim until after her arrival in England.

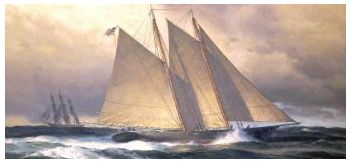

The purpose of fitting out in a French port was to avoid giving Englishmen too much opportunity to study the vessel before she began her racing. This precaution availed little, as events transpired, for a brush with a fast English cutter on the America's first morning in English waters showed what the "glorified pilotboat," as an English writer not inaptly called her, could do. With her first performance in The Solent the history of international yacht-racing gloriously began.

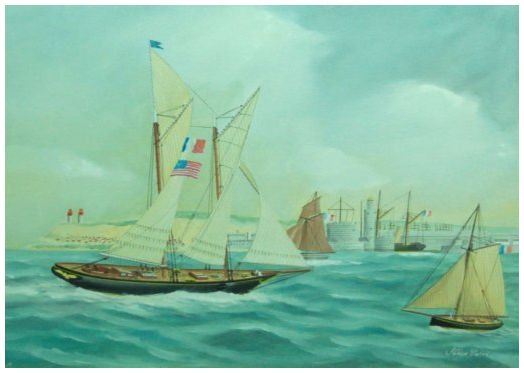

The America, with John C. and Edwin A. Stevens on board, left Havre for England on Thursday July 31st, 1851, and arriving in The Solent that night worked up to about six miles below Cowes, where she anchored, the weather being thick.

The America, with John C. and Edwin A. Stevens on board, left Havre for England on Thursday July 31st, 1851, and arriving in The Solent that night worked up to about six miles below Cowes, where she anchored, the weather being thick.

Commodore Stevens thus described the scene on the America's first morning in English waters, in a speech delivered at a dinner tendered him and his associates at the Astor House, New York, October 2d, 1851 :

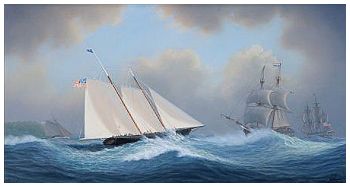

"In the morning the tide was against us, and it was dead calm. At nine o'clock a gentle breeze sprung up, and with it came gliding down the Laverock, one of the newest and fastest cutters of her class.

" The news spread like lightning that the Yankee clipper had arrived, and the Laverock had gone down to show her the way up. The yachts and vessels in the harbor, the wharves, and windows of all the houses bordering on them were filled with spectators, watching with eager eyes the eventful trial. They saw we could not escape, for the Laverock stuck to us, sometimes lying-to and sometimes tacking round us, evidently showing she had no intention of quitting us. We were loaded with extra sails, with beef and pork and bread enough for an East India voyage, and were four or five inches too deep in the water. We got up our sails with heavy hearts ; the wind had increased to a five- or six-knot breeze, and after waiting until we were ashamed to wait longer, we let her [the Laverock] go about two hundred yards, and then started in her wake.

"I have seen and been engaged in many exciting trials at sea and on shore. I made the match with the horse Eclipse against Sir Henry, and had heavy sums both for myself and my friends depending on the result. I saw Eclipse lose tlie first heat and four-fifths of the second without feeling one-hundredth part of the responsibility, and without feeling one-hundredth part of the trepidation. I felt at the thought of being beaten by the Laverock in this eventful trial. During the first five minutes not a sound was heard save, perhaps, the beating of our anxious hearts or the slight ripple of the water upon her [the America's] swordlike stem. The captain was crouched down upon the floor of the cockpit, his seemingly unconscious hand upon the tiller, with his stern, unaltering gaze upon the vessel ahead. The men were motionless as statues, their eager eyes fastened upon the Laverock with a fixedness and intensity that seemed almost supernatural. The pencil of an artist might, perhaps, convey the expression, but no words can describe it. It could not and did not last long. We worked quickly and surely to windward of her wake. The crisis was past ; and some dozen of deep-drawn sighs proved that the agony was over.

"I have seen and been engaged in many exciting trials at sea and on shore. I made the match with the horse Eclipse against Sir Henry, and had heavy sums both for myself and my friends depending on the result. I saw Eclipse lose tlie first heat and four-fifths of the second without feeling one-hundredth part of the responsibility, and without feeling one-hundredth part of the trepidation. I felt at the thought of being beaten by the Laverock in this eventful trial. During the first five minutes not a sound was heard save, perhaps, the beating of our anxious hearts or the slight ripple of the water upon her [the America's] swordlike stem. The captain was crouched down upon the floor of the cockpit, his seemingly unconscious hand upon the tiller, with his stern, unaltering gaze upon the vessel ahead. The men were motionless as statues, their eager eyes fastened upon the Laverock with a fixedness and intensity that seemed almost supernatural. The pencil of an artist might, perhaps, convey the expression, but no words can describe it. It could not and did not last long. We worked quickly and surely to windward of her wake. The crisis was past ; and some dozen of deep-drawn sighs proved that the agony was over.

" We came to an anchor a quarter or perhaps a third of a mile ahead, and twenty minutes after our anchor was down the Earl of Wilton and his family were on board to welcome us, and introduce us to his friends. To himself and family, to the Marquis of Anglesey and his son. Lord Alfred Paget, to Sir Bellingham Graham, and a host of other noblemen and gentlemen, were we indebted for a reception as hospitable and frank as ever was given to prince or peasant."

That the speedy stranger, whose model and rig were new to them, should cause consternation among the English yachtsmen, whose title to yachting leadership had never been questioned, was but natural.

The London Times compared the agitation caused among them by the America, after she had shown Laverock her quality, to that which "the appearance of a sparrowhawk in the horizon creates among a flock of woodpigeons or skylarks."

The Englishmen were free, though not entirely unfriendly, in their criticisms of the America. One writer described her as follows :

"A big-boned skeleton she might be called, but no phantom. Hers are not the tall, delicate, graceful spars with cobweb tracery of cordage scarcely visible against the gray and threatening evening sky, but hardy stocks, prepared for work and up to anything that can be put upon them. Her hull is very low ; her breadth of beam considerable, and the draught of water peculiar, —six feet forward and eleven feet aft. Her ballast is stowed in her sides about her water-lines, and as she is said to be nevertheless deficient in headroom between decks her form below the waterline must be rather curious. She carries no foretopmast, being apparently determined to do all her work with large sheets."

So shy were English yacht owners of the America that Commodore Stevens' challenges for her, posted in the Royal Yacht Squadron's club-house, remained untaken.