Yves GARY Hits: 4382

Category: 1899 : CHALLENGE N°10

THE AMERICA'S CUP WILL REMAIN HERE; COLUMBIA WON BY OVER SIX MINUTES

THE AMERICA'S CUP WILL REMAIN HERE; COLUMBIA WON BY OVER SIX MINUTES Oct. 21, 1899 - The cup is safe, and Columbia is the gem of the ocean. ...

Oct. 21, 1899 - The cup is safe, and Columbia is the gem of the ocean. ...

... The yachting supremacy of the United States is just where it was before the formidable Shamrock was turned out of the brain of Will Fife of Fairlie, and there is a place for another challenger as soon as one can be found who will undertake the task of “lifting” the cup.

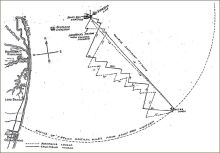

There was a long swell rolling in from the southeast and a little cross sea on its surface with little bunches of cottony crests. The compass course was signaled from the committee boat south by west, the code letters being D. F, G. The committee boat was anchored to the eastward of the lightship, and the Luckenbach was sent away to log the course, the guideboat in the meanwhile taking up a position about a quarter of a mile down the course.

There was a long swell rolling in from the southeast and a little cross sea on its surface with little bunches of cottony crests. The compass course was signaled from the committee boat south by west, the code letters being D. F, G. The committee boat was anchored to the eastward of the lightship, and the Luckenbach was sent away to log the course, the guideboat in the meanwhile taking up a position about a quarter of a mile down the course.

The preparatory gun was fired on time, and the accompanying red ball and blue peter sent up. At this time the boat logging the course, and which was sent away shortly after the course was signaled, was hull down to leeward, with two patent logs reeling off the miles from outriggers fixed to starboard and port on her upper deck.

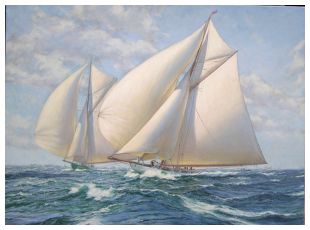

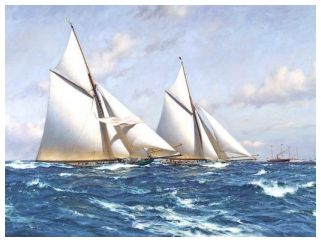

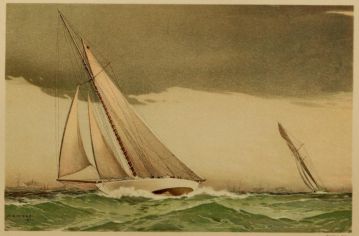

Both yachts were -heeling considerably in the heavy breeze under lower sails only. Each, however, had a working topsail stopped at the mast, awaiting the action of the other like two gladiators watching each other's movements.

Both yachts were -heeling considerably in the heavy breeze under lower sails only. Each, however, had a working topsail stopped at the mast, awaiting the action of the other like two gladiators watching each other's movements.

Six minutes before the starting gun. Shamrock broke out her topsail and headed for the line with Columbia on her weather quarter. The Irish yacht then broke out her staysail and bore away on the port tack. The white wonder also broke out her staysail less than a minute before the warning signal, and eased sheets until she was to leeward and abeam of Shamrock.

Both were heading doe south and heeling at about the same angle. There were sailors aloft on the spreaders of both yachts, and the foam and spray were flying to starboard and port in inspiring style as they buried their decks under the bright waters.

Shamrock went about two minutes before the start and bearing away on the starboard tack, rolled her rail under as she felt the breeze and reached away toward the old red Lightship. Columbia followed on her port quarter, showing the turn of her garboard strake on the weather side as she held up and crossed Shamrock's wake.

Shamrock went about two minutes before the start and bearing away on the starboard tack, rolled her rail under as she felt the breeze and reached away toward the old red Lightship. Columbia followed on her port quarter, showing the turn of her garboard strake on the weather side as she held up and crossed Shamrock's wake.

When she attained that position, she again eased sheets and squared away for the line with spinnaker pole on deck and lying out over the starboard bow ready to be guyed back a moment after slipping between the two stakeboats. Columbia was not footing as fast as her rival, but was pointing up toward the weather end of the line.

Shamrock’s spinnaker pole was lowered to starboard just as Columbia eased sheets and squared away for the windward end of the line, neither having a great deal of time to spare. The Shamrock was first over the mark, and crossed at 11:00:34. Columbia crossed at 11:01:35 to the weather of the wake of the Irish yacht, and at once tried to luff out beyond the flying green hull.

The American yachts’ spinnaker pole was guyed further forward than the one on the Shamrock, and the sail was broken out just as the handicap gun was fired. Sir Thomas' men set their spinnaker twenty-five seconds later than that of the American yacht, and it was guyed aft quickly as the big sail swelled out.

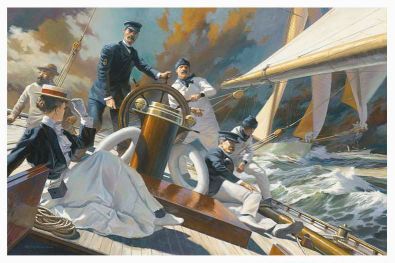

It was different on Columbia, and almost immediately the boom pitch poled and the spinnaker laid across the jibtopsail stay and was almost goose winged. The crew evidently were unable to come up with the after guy, and time and again the tack of the sail raised up and the big expanse of canvas was only kept from drifting across the stay and fouling the entire headgear by bearing away, keeping the sail full and trusting to the fact that the puffs did not continue for any great length of time.

In the meantime Shamrock's sails were drawing beautifully, and her crew, clad in oilskins, gathered aft and watched the antics of the unruly spinnaker that kept the men on Columbia busy clearing it, as it curled ever the stay at every puff. At last the crew tailed on the guy, and brought the sail art. Even then the sail had a tendency to rise, and kept the spectators’ nerves on edge for fear it would carry away something. The whole sail was lifted high in the air, its foot being about half-way up to the head of the lower mast. The strain was tremendous, but Capt. Barr did not like the looks of the flying Shamrock so far ahead, and broke out his working topsail at 11:10:30.

In the meantime Shamrock's sails were drawing beautifully, and her crew, clad in oilskins, gathered aft and watched the antics of the unruly spinnaker that kept the men on Columbia busy clearing it, as it curled ever the stay at every puff. At last the crew tailed on the guy, and brought the sail art. Even then the sail had a tendency to rise, and kept the spectators’ nerves on edge for fear it would carry away something. The whole sail was lifted high in the air, its foot being about half-way up to the head of the lower mast. The strain was tremendous, but Capt. Barr did not like the looks of the flying Shamrock so far ahead, and broke out his working topsail at 11:10:30.

The strain on the backstays was great, and had there been a flaw in a single strand the groaning topmast would have toppled over forward in the twinkling of an eye. Slowly, almost imperceptibly, the American boat began to gain, but at 11:24 the spinnaker again arose high in the air and flopped once more across the stay. It was quickly brought back in position, however, and she fairly flew along in the wake of the emerald beauty and rapidly overhauled her.

At 11:26:21 Shamrock doused her jib and set a smaller one and a baby jib topsail, making ready to take in her spinnaker and enter a luffing match, should Columbia try to pass to windward. Capt. Barr did not care to bother about it, however, and held his true course. Columbia was on even terms at 11:53.  She as some distance to leeward and Shamrock bore away in order to blanket the craft that tore through her lee like a nautilus and with the speed of a swallow.

She as some distance to leeward and Shamrock bore away in order to blanket the craft that tore through her lee like a nautilus and with the speed of a swallow.

Her advantage was short-lived, however, for when the Irish craft bore away she increased her speed, and again coming up abreast of Columbia, forged once more in the premier position. She opened up a gap of clear water again, and for a short time the admirers of the cup hunter saw an opportunity of the great American eagle losing a few tall feathers, but their joy was doomed to come to a sudden end, for some kindly sea serpent or other intangible and unseen power carried Columbia again abreast of the little green boat. After holding that position for a few minutes, she again drew away under the influence of a momentary puff and opened up a gap that she increased every minute as she shot straight as an arrow toward the outer mark that was plainly visible tumbling and tossing on the heaving sea scarcely a mile away.

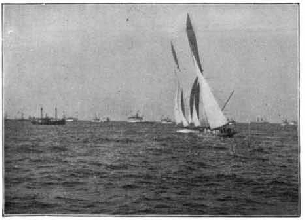

The steady seventeen-knot breeze sweeping across the waters had kicked up quite a sea in the vicinity of the outer mark, and the excursion boats rolled and reeled in the white-capped waves. Columbia held her lead beautifully and the Shamrock sobbed along in her wake.

The steady seventeen-knot breeze sweeping across the waters had kicked up quite a sea in the vicinity of the outer mark, and the excursion boats rolled and reeled in the white-capped waves. Columbia held her lead beautifully and the Shamrock sobbed along in her wake.

At 12:18:20 Columbia's crew let go outhaul and halyard of the spinnaker and smartly smothered the writhing sail. Shamrock followed suit just as Columbia's working topsail was sent down on deck. Columbia flattened sheets, leaving the tossing red disk or the starboard hand at 12:19, and making a wide turn, reached away toward the beach, her crew huddled up under the weather rail and her port deck awash almost to the handrail on her deck.

Shamrock still carrying her little topsail, made a beautiful sweep and tacked around the mark seventeen seconds after the white phantom that was racing in toward Long Branch with the speed of a pigeon fresh from a trap.

Both yachts luffed sharp up into the wind and flattened sheets. Columbia made two or three sharp luffs, while Shamrock was kept away and romped off till she was on Columbia's lee quarter. The British yacht kept her gaff topsail aloft,. but it did her no good whatever. Columbia's crew set up her peak after rounding, and after that she worked very fast. She began to outpoint Shamrock in n manner that was most encouraging to see.

The yachts were now showing the same relative merits as they had shown in light airs. Columbia was working slowly but surely out to windward of her rival, and the speed of the two through the water was about the same. If the challenger had been pointed as high as Columbia she would have tailed to go as fast.

At 12:30 Shamrock let go her topsail sheet and gathered the useless sail in to the mast. She was sailing on her beam ends at the time, and the sail was a bag in which the wind found no comfortable resting place. The wind was now singing through the rigging of both yachts in a manner that would have given a landsman the cold shivers, and which probably was inspiring to the real sailor men on the racers.

At 12:30 Shamrock let go her topsail sheet and gathered the useless sail in to the mast. She was sailing on her beam ends at the time, and the sail was a bag in which the wind found no comfortable resting place. The wind was now singing through the rigging of both yachts in a manner that would have given a landsman the cold shivers, and which probably was inspiring to the real sailor men on the racers.

After the topsail had been sent down on deck, Shamrock stood up better, but her pointing was not improved at all. Columbia continued to outwind her opponent, pointing better by a quarter of a point. The two yachts were heading directly for the West End Hotel at Long Branch.

The more it blew and the more the rising sea pounded under their weather bows, the more Shamrock fell off to leeward. In his efforts to get the better of this unfortunate tendency of the challenger Capt. Hogarth put her on the port tack at 12:40. Capt. Barr followed suit with Columbia at 12:41:15. At this time the scene was one of the most inspiriting that has been seen in a yacht race in these waters in recent years.

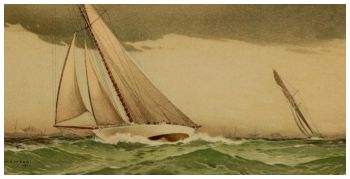

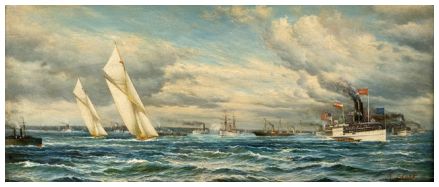

The green seas were standing up straight and the wind was tearing the tops off them and sending the water down to leeward in driving sheets of smoky spoondrift. The whole surface of the sea was torn up into a foaming field of white and green, in which the sunlight sowed great patches of golden yellow. The excursion steamers were churning the water astern of them into acres of emerald green and sapphire blue in their efforts to keep up with the yachts, and the torpedo boats and revenue cutters were pouring huge steams of black smoke from their funnels as they rushed away toward the lightship.

The green seas were standing up straight and the wind was tearing the tops off them and sending the water down to leeward in driving sheets of smoky spoondrift. The whole surface of the sea was torn up into a foaming field of white and green, in which the sunlight sowed great patches of golden yellow. The excursion steamers were churning the water astern of them into acres of emerald green and sapphire blue in their efforts to keep up with the yachts, and the torpedo boats and revenue cutters were pouring huge steams of black smoke from their funnels as they rushed away toward the lightship.

Shamrocks mainsail showed a big bone in it near the leach, while Columbia's leach shook like an aspen. The head of her staysail also shook often, but this was from easing her in the puffs. At 12:45, as the two were standing off on the port tack, with Long Branch up on their weather quarters, Columbia had 300 yards of open water between the end of her boom and Shamrocks nose pole. At the same time the American yacht was holding a course about 200 yards to windward of that held by her antagonist.

The yachts were doing about seven knots an hour through the water, and were making equally good weather of it. The American yacht keeled a little more than her opponent, and was eased to the puffs a little more frequently. Shamrock, on the other hand, was sailed with more boldness, but she would drop off to leeward. Her fast footing was all that saved her from a much worse defeat than she received.

The yachts were doing about seven knots an hour through the water, and were making equally good weather of it. The American yacht keeled a little more than her opponent, and was eased to the puffs a little more frequently. Shamrock, on the other hand, was sailed with more boldness, but she would drop off to leeward. Her fast footing was all that saved her from a much worse defeat than she received.

Shamrock went on the starboard tack at 12:55:45 and Columbia followed suit at 12:56:15. The American champion was now a quarter of a mile dead to windward of her opponent and barring the loss of her mast, was a sure winner. On the starboard tack Columbia pointed fully half a point better than her opponent, except when headed off by the head flaws familiar to all sailors.

Columbia was rapidly converting the lead of a quarter of a mile into half a mile. It appeared as if the American yacht was going where she was pointing while Shamrock was moving sidewise like a crab toward the New Jersey coast. Sympathy for Sir Thomas Lipton was widespread, but at the same time the race as a test of comparative merits of the two vessels was rapidly degenerating into a farce. No challenger for the historic cup had ever been put so far leeward in so short a lime.  At 1:10 Columbia was a mile ahead of Shamrock and still gaining. The wind continued to blow at a fine pace, and, as Capt. Evans curtly remarked, “ Any yachtsman who wishes for more wind than this is a hog."

At 1:10 Columbia was a mile ahead of Shamrock and still gaining. The wind continued to blow at a fine pace, and, as Capt. Evans curtly remarked, “ Any yachtsman who wishes for more wind than this is a hog."

As they stood in for the New Jersey beach it could be seen that the American yacht was heading for Rumson Beach, while the other yacht was heading a mile lower. At 1:17:30 Shamrock went on the port tack and Columbia followed. At 1:19 Shamrock went on the starboard tack. Columbia followed at 1:20:15, and Shamrock immediately took the port tack. It was Capt. Hogarth’s evident intention to lead Capt. Barr into a contest at short tacks, and at 1:22:45 Columbia went on the port tack. Shamrock immediately went on the starboard tack.

This was a very feeble attempt, indeed, for the two had had a contest once before at the short-tack game and Shamrock had been worsted. Columbia went on the starboard tack at 1:26 and Shamrock instantly took the port tack. The wind had temporarily fallen lighter and a huge gray cloud drifting down out of the north shadowed the blue sea and turned it to a greenish gray. The scene for a time had a genuine Autumn look, and presently there was a little rift in the cloud and the sun peered through, filling the lowlands in the west and the flying hillows of the sea with a flood of silver.

This was a very feeble attempt, indeed, for the two had had a contest once before at the short-tack game and Shamrock had been worsted. Columbia went on the starboard tack at 1:26 and Shamrock instantly took the port tack. The wind had temporarily fallen lighter and a huge gray cloud drifting down out of the north shadowed the blue sea and turned it to a greenish gray. The scene for a time had a genuine Autumn look, and presently there was a little rift in the cloud and the sun peered through, filling the lowlands in the west and the flying hillows of the sea with a flood of silver.

At 1:30:30 Columbia went on the port tack a mile ahead of her rival. Shamrock responded by going on the starboard tack, and at the same instant the sun fell on the lee side of her mainsail, throwing it out in a great crescent of gold against the purple Highlands.

At 1:35:30 Columbia went on the starboard tack and Shamrock immediately broke tacks with her. As the wind had fallen light, it seemed remarkable that Shamrock did not set her topsail again. She needed more driving power if ever a yacht did, and the puffs were not strong enough to have buried her rail too deeply. The breeze was still a good one, say twelve miles an hour, and there seemed to be no reason to doubt that the struggle for the cup would be ended before 2:30.

At 1:37:30 Columbia went on the port tack and stood off to sea again. At 1:40:45 Shamrock went on the starboard tack and headed in toward the Highlands. Columbia was now about abreast of Seabright and Shamrock was a mile further down the coast. At 1:45 Shamrock set a club topsail.

At 1:37:30 Columbia went on the port tack and stood off to sea again. At 1:40:45 Shamrock went on the starboard tack and headed in toward the Highlands. Columbia was now about abreast of Seabright and Shamrock was a mile further down the coast. At 1:45 Shamrock set a club topsail.

At 1:48:30 Shamrock went on the port tack. It began to breeze on again, and Shamrock was heeling strongly. The wind came out of a white spot up in the north in a solid puff and tore the ocean up into a writhing sheet of green and white. At 1:55 Columbia got a shift of wind which headed her off 2 points, and she responded by going about. The puff of the squall was too much for Shamrock’s club topsail to carry, and she was luffed and sailed narrow, so that the topsail was aback. The wind got up to about twenty miles an hour in the puffs.

At 2:02:15 Columbia went on the port tack. Shamrock was able to gain a little on Columbia by the aid of the increased speed given by her club topsail, but it was in footing and not in pointing, and America's champion was still far ahead and a very safe winner. Her people wisely kept to their lower sails, for the sky up to windward was a steely gray and the sea was a mass of white foam. Columbia was now a fat half mile to windward. She was lying down so that she carried a smother of white water all along the lee side of her deck.

At 2:02:15 Columbia went on the port tack. Shamrock was able to gain a little on Columbia by the aid of the increased speed given by her club topsail, but it was in footing and not in pointing, and America's champion was still far ahead and a very safe winner. Her people wisely kept to their lower sails, for the sky up to windward was a steely gray and the sea was a mass of white foam. Columbia was now a fat half mile to windward. She was lying down so that she carried a smother of white water all along the lee side of her deck.

Shamrock was sailing at a magnificent speed and was plainly benefiting by the smoother sea. At 2:15 the challenger from a position fully a mile astern of Columbia had worked up to a position abeam of her, though a good distance to leeward. It must have made Capt. Hogarth pretty sad to think he had not sent up his club topsail earlier, for it was of much benefit to his yacht.

On the other hand. Capt. Barr showed good Judgment in keeping to his lower sails. He was pointing much higher than Shamrock and going quite fast enough. The wind held fresh and the puffs were heavy. Shamrock having got up abeam of Columbia did not seem to gain as much as before probably because she was pointed too high. All the excursion boats and yachts were now massed near the lightship which the racers were rapidly approaching. The two were close enough together to make the finish a magnificent sight and as they tore through the water all spectators felt repaid for their long wait.

Shamrock went on the starboard tack at 2:31:10 and Columbia followed at 2:31:55. Shamrock in a few seconds returned to the port tack. And now began the final struggle. Nothing was left for the Captain of the defeated yacht to do but to try once more to make a little ground by the employment of short tacks. Indeed, he did not dare to stand very long on one tack for fear of falling too far to leeward.

Shamrock went on the starboard tack at 2:31:10 and Columbia followed at 2:31:55. Shamrock in a few seconds returned to the port tack. And now began the final struggle. Nothing was left for the Captain of the defeated yacht to do but to try once more to make a little ground by the employment of short tacks. Indeed, he did not dare to stand very long on one tack for fear of falling too far to leeward.

The long reach of Shamrock on the port tack off the New Jersey coast had been the end of her exhibition of good qualities. It was the final spurt of the beaten boat. She now ceased to give the impression of ability to gain anything on the wonderful production of the Bristol designing board.

At 2:3-1:45 Columbia went on the port tack and stood for the mark, to see whether she could fetch it. Just fifteen-seconds later Shamrock went on the starboard tack, and it now became painfully evident to her admirers that she was losing ground at every stretch. The wind was still a fine one, and both yachts were going through the water as if they had steam to propel them.

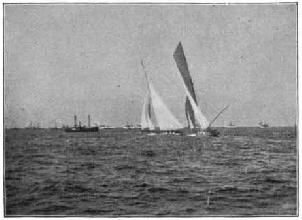

At 2:36:45 Columbia made what was at once seen to be her last tack in the contests for the America's Cup in the year 1899. She went on the starboard tack and stood for the finish line with her lee rail awash and every inch of her snowy canvas drawing like mustard plasters in the heat of a Summer fever.

At 2:36:45 Columbia made what was at once seen to be her last tack in the contests for the America's Cup in the year 1899. She went on the starboard tack and stood for the finish line with her lee rail awash and every inch of her snowy canvas drawing like mustard plasters in the heat of a Summer fever.

As the defender of the cup was nearing the line at a glorious pace, Shamrock at 2:39:45 went on the port tack and it was plainly evident that she was falling to leeward at a discouraging gait. Meanwhile the champion was rushing toward the line, and at 2:40 she tore across it like an express train, while the accompanying fleet gave vent to the feelings of the patient spectators in long-drawn whistles.

Shamrock, after losing more ground by reason of her inability to hold on the wind, went on the starboard tack at 2:44:05 and stood for the line. She was pinched unmercifully to make her weather the lightship, and she succeeded in doing so only by the use of the highly valuable pilot's luff or half board. She at last managed to cross at 2:45:17 and the races for the America's Cup were at an end at the conclusion of the third week. Both boats hauled down their sails after crossing the line, and were towed in their anchorages in the Horseshoe.

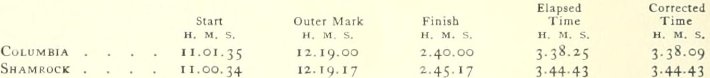

The official summary :

Columbia gained on the first leg 1 m. 18 s., on the second leg 5 m., and won by G m. 34 s.

In the run from the start to the outer mark, Columbia occupied 1 hour 17 minutes and 25 seconds and Shamrock 1 hour 18 minutes and 43 seconds; Columbia's gain 1 minute 18 seconds. On the beat from the outer mark to the finish, Columbia's time was 2 hours and 21 minutes_ and Shamrock’s 2 hours and 26 minutes; Columbia's gain, 5 minutes. Columbia beat Shamrock over the course, 6 minutes and 18 seconds actual time, and 6 minutes and 34 seconds corrected time.

In the run from the start to the outer mark, Columbia occupied 1 hour 17 minutes and 25 seconds and Shamrock 1 hour 18 minutes and 43 seconds; Columbia's gain 1 minute 18 seconds. On the beat from the outer mark to the finish, Columbia's time was 2 hours and 21 minutes_ and Shamrock’s 2 hours and 26 minutes; Columbia's gain, 5 minutes. Columbia beat Shamrock over the course, 6 minutes and 18 seconds actual time, and 6 minutes and 34 seconds corrected time.

Before the Columbia had crossed the finish line Sir Thomas had gathered his guests below, and over the wine that had been intended for the Shamrock proposed a toast to "the better boat, her owners, and her crew. "

“The better boat won,“ he said, “ and that is as it should be and has always been in the races for the America's Cup."

“The better boat has won,” said Sir Thomas Lipton in proposing a toast to the defender, “ but I have it in mind to challenge again unless some other Englishman should wish to do so." The sentiments were as enthusiastically cheered by his guests as if another challenger was already speeding westward over the ocean bearing England's hopes.

Publié le 21 0ctobre 1899 |

THE AMERICA'S CUP WILL REMAIN HERE. |

||

Publié le 21 0ctobre 1899 |

THE AMERICA'S CUP WILL REMAIN HERE |

||

Publié le 18 Octobre 1899 |

THE CUP STAYS HERE. |

Page |

Page |

Publié le 21 0ctobre 1899 |

LIPTON’S ATTEMPT TO LIFT THE CUP HAS FAILED. |

Page |

Page |