Yves GARY Hits: 1370

Category: 1899 : CHALLENGE N°10

SLOOP TO CUTTER-SLOOP - © 1899 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, INC : OCTOBER 14, 1899

SLOOP TO CUTTER-SLOOP - © 1899 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, INC : OCTOBER 14, 1899In the first, or schooner period of the cup contests, extending from 1851 to 1881, there was no such clearly defined struggle of type against type as was witnessed in the later races of the second period, when the English yachtsmen received some consolation for their successive defeats in knowing that their American competitors, in the struggle to retain the "America" cup, have been forced to abandon the time-honored centerboard and adopt the lead-ballasted keel.

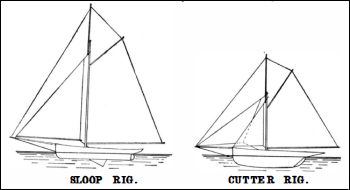

Although the shifting centerboard in the sloop, and the lead- ballasted keel in the cutter, constituted the radical difference between the two types as they existed in the seventies, they were by no means all the difference; for it is a fact that the rig and sail-plan of the two types showed as great variation as their models. This will be evident from a comparison of the two diagrams herewith presented.

The sloop rig was distinguished by great length of mainmast and a relatively short topmast. The mainsail had a lofty hoist, the gaff was peaked rather low, and the sail was laced to the boom. There was a single headsail, which was also laced at the foot to a boom. The bowsprit was a permanent fixture in the bows and it had a pronounced upward rake.

The sloop sail plan may be described as being lofty and narrow. The cutter rig, on the other hand, was relatively low and broad. The main mast was short and the topmast long. The mainsail had a short hoist, but the long gaff was peaked high, giving a better set to the canvas for windward work. The mainsail was hauled out taut to the end of the boom, but was not laced to the boom as in the sloop. The area forward of the mast was divided between two sails, a jib and foresail, neither of which carried a boom. The bowsprit could be reefed inboard in heavy weather.

The sloop was distinguished by shoal draught and great beam, as distinguished from the cutter of that day, which, under the influence of the Thames rule of measurement for time allowance, by which a penalty was placed upon beam but none upon draught, had grown to be deep and extremely narrow.

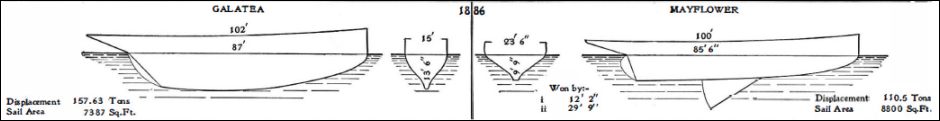

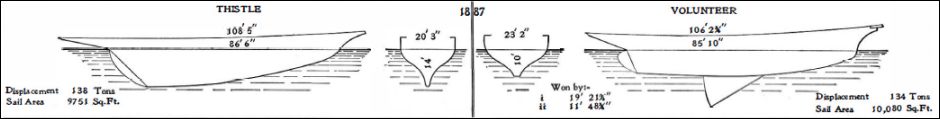

This extreme narrowness, it should be said, was purely the result of the Thames rule, for the earlier English cutters were as beamy as the American sloops, as may be seen in the case of the cutter “Arrow, " built in 1832, which on a length of 61 feet 9½ inches had a beam of 18½ feet, and in the "Mosquito," built in 1848, which, with a waterline length of 59 feet 2 inches, had a beam of 15 feet 3 inches. The Thames rule, adopted by the Yacht Racing Association in 1879, produced a “plank on edge" type of cutter, and the ratio of beam to length decreased until in the “Tara" the beam was only one-sixth the length. The Thames rule continued in force until after the Genesta and Galatea had raced for the “America" cup. As soon as it was replaced by a rule in which the penalty on beam was removed, we see a return to the more reasonable proportion of an earlier day, the Thistle (see accompanying diagram) having a beam of 20 feet on a waterline length of 86½ feet.

The sloop depended for its stability upon breadth of beam, the cutter upon outside lead ballast, bolted to the bottom of the keel. The sloop had great initial stability; but after she passed a certain angle of heel, the margin of stability rapidly decreased, until a vanishing point was reached, beyond which capsize was inevitable. The keel cutter had small initial stability, but as she heeled the righting moment of the lead keel increased, until it was at a maximum, when she experienced a “knock-down." The displacement of the sloop was relatively small, that of the cutter relatively large. The sloop, by virtue of her initial stability, could carry an excessive sail spread, that of the cutter was relatively small. The one was an ideal light-weather boat, the other was at her best in a strong blow.

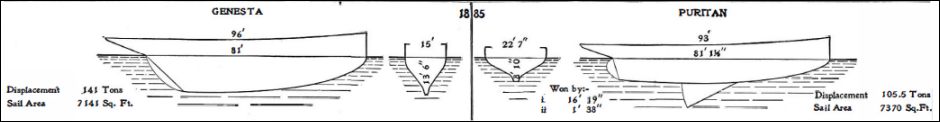

Early in the year 1885, a challenge for the “America's" cup was sent to the New York Yacht Club through the Royal Yacht Squadron by Sir Richard Sutton, the owner of the crack keel cutter "Genesta," which had defeated with comparative ease the fleetest craft of her kind in British waters. It was quickly recognized that there was no sloop afloat in American waters that could hope successfully to meet the challenger, and hence two sloops, the Priscilla and the Puritan, which embraced the latest improvements in this type of vessel, were constructed; and after a series of competitive races the Puritan was selected to defend the cup. The Genesta was a typical "Thames measurement" deep keel cutter, 81 feet on the water line, 15 feet beam, and 13 feet 6 inches draught. The Puritan was a marked departure from the national type, of which she retained only the characteristic features of great beam, shallow hull, and centerboard. She carried the cutter rig practically in its entirety and also the cutter outside lead, 32 tons of this useful metal being bolted to the bottom of her keel. With a displacement smaller than that of the Genesta by 36 tons, she carried a slightly larger sail spread.

In the first race the Puritan fouled the Genesta in the attempt to cross her bow when the latter boat had the right of way. The Puritan was ruled out on the spot and the race given to the Genesta with the privilege of sail over, but Sir Richard Sutton, with characteristic sportsmanship, refused the privilege and set a precedent which may well govern all such unfortunate contingencies in future races. The first race ultimately came off on September 14, 1885, in a light and fluky wind, and the shallow, light displacement boat won easily by 16 minutes and 19 seconds. The second race resulted in one of the most exciting and memorable contests in the history of the struggle for the cup. The course was twenty miles to leeward and return, and the Genesta rounded the outer mark fully an eighth of a mile ahead. On the twenty mile close-hauled thrash to the home mark, the wind freshened and offered a splendid opportunity to test the windward qualities of the two types of vessel. The Puritan, seeing the probability of an increase in the weight of the wind, took in her topsail and housed her topmast; but the cutter clinging to her topsail and heeling down to the wind until the 70 tons of lead in her keel could get in its steadying effect, began to make a splendid exhibition of cutter work in the favorable cutter weather.

The Puritan under her snugger canvas, and with the incomparable centerboard to edge her up into the wind, began steadily to overhaul her rival, and sailing up into the weather berth, she came romping home the winner of a magnificent race by the close margin of 1 minute and 38 seconds.

The following year witnessed races between the cutter Galatea, owned by Lieut. Henn, and the centerboard sloop Mayflower, which, like the Puritan, was owned by General Payne, of Boston. After the defeat of the Genesta by the Puritan, but little apprehension was entertained regarding the visit of the "Galatea," as she was known to be an inferior vessel to her predecessor. The victory of the "Mayflower" over the "Galatea" was complete, the centerboard sloop beating the keel cutter by 12 minutes and 2 seconds in the first race and in the second race by 29 minutes and 9 seconds.

The impossibility of winning the "America" cup with a yacht built under the restrictions of the Thames rule of measurement led to the adoption of a new rating rule based on water length and sail area, which resulted in a return to the broader beam that characterized the earlier English cutters of the Mischief and Arrow type. The effect was noticeable in the next challenger, the Scottish yacht Thistle, which with 5 feet more beam than the Galatea, and about 20 tons less displacement, carried 2, 400 square feet more sail. The Thistle came to America in 1887, with a record of being by far the fastest cutter in British waters, and the supreme confidence of the syndicate of Clyde yachtsmen who owned her was only equaled by the dismay which the record of her victories carried to the hearts of many American yachtsmen. The eyes of the yachting world turned instinctively to General Payne, and the brilliant designer of Puritan and Mayflower, Mr. Burgess, of Boston. Results proved that their confidence was not misplaced. The Volunteer, as the new craft was named, showed a further development along the lines upon which Mr. Burgess had worked in the Puritan and Mayflower. The draught had increased to 10 feet, and the outside lead, or rather, in this case, the lead that was run into the deep, hollow keel, amounted to 50 tons.

The sail plan of the Volunteer was by far the largest ever spread on a single sticker, and in the preparatory trial races she had no difficulty in vanquishing the two preceding cup defenders.

In the days of the Thistle and Volunteer contest there was the same anxiety as to the fate of the cup which is noticeable in the present Shamrock and Columbia contest. In the very first race, however, sailed in a light breeze, the Volunteer came home with a margin of 19 minutes and 21 seconds to her credit. Then, as now, the challenger was reputed to be a perfect glutton for heavy weather, and the Thistle contingent prayed for the strong wind which was necessary to drive the Scottish champion to victory. It came in the second race, which was held over the outside course ; and in a thrash of fifteen miles to windward and return it was found that the Volunteer liked a piping breeze just a little better than the Thistle. She lay so much closer to the wind and footed so much faster than the cutter as to turn the outer mark 14 minutes ahead. She lost somewhat on the run home, but finished in the lead by 11 minutes and 48 seconds.

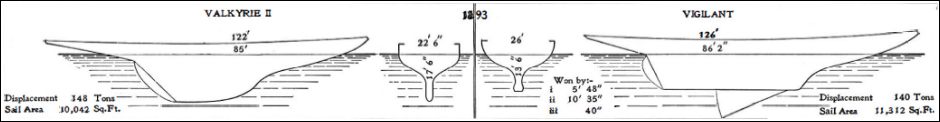

The “America's" cup was destined to repose in the lockers of the New York Yacht Club undisturbed for the next six years, or until the year 1893, when Valkyrie II, owned by Lord Dunraven and designed by G. L. Watson, was sent over the water with the Godspeed of all England behind it. The Valkyrie II was a further development in the direction of greater beam and shallower under-water body. In her profile she showed the growing tendency among English designers to reduce the wetted surface of the boat, and hence the “skin friction," by removing all useless "dead-wood." The keel forward was cut away until little was left but the hull proper, and the helm was placed well in toward the center of the boat and given a rake approaching an angle of forty-five degrees.

This reduction of the lateral plane resulted in an under-water form which offered a minimum of resistance to turning when the boat was coming about; a quality which stood Valkyrie II in good stead when she was maneuvering for the start, or when she had the Vigilant placed under her lee in the windward leg of a race. The Vigilant was a still further development along the sloop cutter lines. On a waterline length of 86 feet 2 inches, her beam reached the unprecedented width of 26 feet, and the great draught for a sloop of 13 feet 6 inches, which, by the way, was equal to that of any previous challenger. Her total sail spread was 11,312 square feet, or 1,270 square feet more than that of Valkyrie II. She had 55 tons of lead in her keel in addition to 29 tons of inside ballast. The Vigilant served to introduce Mr. Herreshoff as a builder of cup defenders and she contained many of the original features which had characterized Mr. Herreshoff's past boats, the Gloriana, Wasp and Navahoe. She had exceptionally long over-hangs and measured 126 feet overall.

She had lofty topsides and in every way was a marked departure from the model of Mr. Burgess’ sloops. Her under-water body was built of Tobin bronze and her topsides of steel plating.

The first race, which should have been to windward and return, was marked by a change of the wind, which veered so as to make the race a reach in both directions, and Valkyrie II was beaten 5 minutes awl 48 seconds. The second race over a triangular course was sailed in a strong whole-sail breeze, and the Vigilant drew away steadily from the very start, winning by 10 minutes and 45 seconds. The third race, 15 miles to the windward and return, was sailed in a reefing wind and a rather heavy sea. It proved one of the greatest, surprises in the history of yachting, for to the astonishment of the advocates of the centerboard, the deep keel cutter not only began to beat out to windward of the centerboard, but she footed faster through the water, and the crowds on the assembled excursion boats were treated to the unwonted sight of a centerboard boat being beaten on her strongest point of sailing. Valkyrie II turned the outer mark with a lead of 1 minute and 55 seconds, and as they started away for home, the wind increasing, it became a question whether the big sail spread of the Vigilant would enable her to overhaul her smaller opponent. She gained rapidly, but would have failed to close the gap and save her time allowance of 1 minute and 33 seconds, had it not been for the extraordinary ill luck of the challenger; for the Valkyrie's spinnaker, which had been torn slightly in setting, was blown to shreds in the strong wind, and a second spinnaker met with a like fate. The Vigilant passed her and managed to save her time allowance with just 40 seconds to spare.

The year 1893 was certainly a banner year in respect of the great influence which It exerted upon the science and art of yacht designing and construction, particularly with regard to the famous keel and centerboard controversy; for it happened that while Herreshoff and Watson were fighting it out with Vigilant and Valkyrie at Sandy Hook, there was a battle royal in progress in the English Channel between two other creations of these designers, the Navahoe and the Britannia, which were practically sister boats to those two yachts. The outcome was strongly in favor of the keel cutter. The Navahoe was built by Herreshoff for Mr. Royal Phelps Carroll, for the purpose of challenging for several well-known English cups, but particularly for the purpose of winning back the Brenton's Rief and Cape May cups which bad been carried cross the water by the challenger of 1885, the Genesta. The results, especially when the Navahoe met the Britannia, proved the superiority of the keel type. When pitted against the Satanita and Fife's Calluna, the Navahoe could hold her own but in windward work against Britannia she was hopelessly out classed.

In the contest for the Royal Victoria Yacht Club cup the Britannia won the first race, sailed over a 50-mile course, by 16 minutes and 30 seconds. The second race, Britannia won by 34 minutes and 30 seconds and the third race, by 15 minutes and 8 seconds.

In her next race, which was for the recovery of the Brenton's Reef cup, the Navahoe was more successful. The course was from the Needles across the English Channel to Cherbourg and back, a distance of 120 knots, and the race was sailed in a strong beam wind and a heavy sea, both boats having their mainsails reefed down. It was a reach from start to finish, and the boats were never separated by more than a few boats' lengths. The Britannia finished a few seconds in the lead. The cup committee, however, had moved the stake boat into a more sheltered, position within the Needles, and Mr. Carroll having entered a protest, the cup was awarded to the Navahoe. The race for the Cape May cup was sailed over the same course, and was won by the Britannia with 36 minutes and 23 seconds to spare.

In the following year the Vigilant crossed the ocean to avenge her twin sister; but she met with six successive defeats in the first races in which she engaged, at the hands of the same Britannia. In later races, however, she did better, the final score between the two boats standing at eleven in favor of the Britannia against six for the Vigilant. It was the same remarkable quickness in stays and the same fine windward qualities shown by the other Watson boat, Valkyrie II , that carried Britannia so frequently to victory against Navahoe and Vigilant. Mr. Herreshoff was aboard the Vigilant during the third race against Valkyrie II in 1893, and he was aboard her frequently in 1894, when Britannia so often had her under her lee, and the lesson of this experience was not likely to be lost in subsequent cup races. It was evident that the day of the centerboard in the "America" cup contests was over and it was with no surprise that yachtsmen learned in 1895 that the new defender of the "America" cup was to be a keel boat.

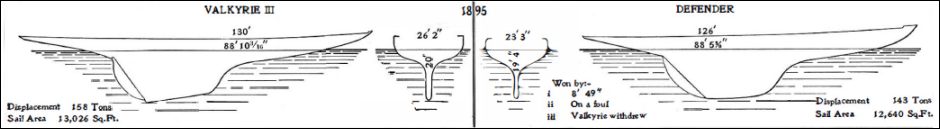

The next challenger, Valkyrie III, was an enlargement of Valkyrie II, with greater draught, 20 feet as against 17½ feet, with an increase of over 3½ feet in the beam, and the enormous increase in sail area of 3,000 square feet. It looked, indeed, when Valkyrie III appeared in these waters, as though Mr. Watson had determined to out-Herod Herod in the matter of beam and sail area, for the new cutter was of a greater beam than any previous cup defender, and for the first time in the history of the cup races the challenger possessed the greater sail area. She was in every way an extreme boat. The midship section of Valkyrie III shows the influence of the Vigilant on Mr. Watson in the matter of extreme overhangs, and excessive beam. Following along lines on which he worked in the Thistle and Valkyrie II he had greatly increased the beam, cut further into the lateral plane, both fore and aft, and increased the draught by 2½ feet, the maximum draught of Valkyrie III reaching the great depth of 20 feet. On the other band, the influence of the races of 1893 and 1894 on Mr. Herreshoff is seen in the comparison of the midship section and sheer plan of Defender with that of Vigilant and Valkyrie II. As compared with Vigilant he has abandoned the great power beam, moderate draught (moderate as compared with the deep keel cutters), the long, straight keel, the small rake of the stern post and rudder; and as compared with Valkyrie II, he has adopted the moderate beam, the deep draught (in the case of the Defender no less than 5½ feet more than that of the Vigilant), the short rocketed keel, and the raking stern post placed well in under the boat. But as a final and most startling innovation of all in an international “America" cup champion, he has thrown out the national, time-honored centerboard. The genius of Mr. Herreshoff and his originality, however, were shown in the matter of the construction, in which his knowledge of the strength of materials and their structural possibilities gave him a vast advantage, and, indeed, practically won a race for the Defender before the ships had crossed the starting line. By using a high quality of bronze for the underbody of the ship and an aluminum alloy for the topsides, the deck frames and general fittings, he saved at least 7 tons dead weight in the structure of the hull. It is safe to say that the Defender was by far the lightest sailing yacht that had ever been constructed in the history of yacht-racing. In the first race, which was to have been 15 miles to windward and return, the wind shifted, as it so frequently does over this course, so as to the windward and leeward work into reaching. Going to the outer mark in what windward work there was the boats seemed to be very evenly matched; but immediately on turning the mark, the Defender in a reaching wind literally ran away from Valkyrie III and won the race by 8 minutes and 49 seconds. In the second race over a 30-mile triangular course, Valkyrie III in straightening for the line fouled the Defender and carried away her topmast starboard spreader, springing the topmast and seriously crippling the boat. The Defender however, sailed over the course and actually gained 15 seconds on one leg and 1 minute and 17 seconds on the last leg of the trial, losing the race by only 48 seconds. This was a virtual victory for the Defender and removed any doubt as to her superiority. At the last race of the series, Lord Dunraven, the principal owner of Valkyrie III crossed under reduced canvas in order to make the race count as one of the series, but immediately withdrew, his ostensible reason being that the course was overcrowded with excursion boats.

This brought to a close the most disappointing and unsatisfactory series of races in the history of the "America's" cup; but that the Defender is a superior boat to the Valkyrie III was proved to the satisfaction of all yachtsmen who witnessed the contests.

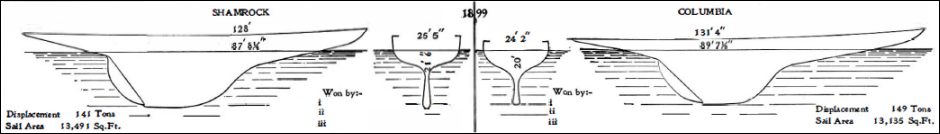

Four years have elapsed since Valkyrie III was dismantled and laid up to rot in an English yard. The present revival of interest in the cup contests is due to Sir Thomas Lipton, whose challenge was sent through the Royal Ulster Yacht Club of Belfast. It was the intention of Sir Thomas to have the challenger built in Ireland and manned by an Irish crew. Hence she was given the suggestive name of “Shamrock." It was realized, however, that in order to construct a yacht to match the constructive skill of Herreshoff, it would be necessary to go to a builder of torpedo boats, and accordingly the order was placed in the Thornycroft yards. The Shamrock introduced another designer into the cup contest in the person of William Fife, Junior, whose success in the smaller classes has placed him in the very front rank on the other side of the water. The order for the American yacht was of course given to Herreshoff, and the result was the most beautiful example of yacht designing and construction ever seen in the history of the contest.

The two boats are so fully discussed in our editorial columns that it is unnecessary to add anything further in the present article. We will close by drawing attention to the fact that, in the form of their hulls, the American and English yachts of 1899 exhibit a curious transposition of ideas as compared with the "America" and her competitors of 1851. The rather full bow, the deep body and the long, fine run and tapering stern of the "Columbia" are somewhat suggestive of the cutter model of half a century ago. On the other hand, the long, sharp entrance, combined with the full quarters and stern of the Shamrock are equally suggestive of the old America. This comparison is drawn, of course, without any reference to the deep fin keels, and is merely offered to show that, as regards many features in the form of the hulls, the types have crossed in the gradual development of the past fifty years.