Yves GARY Affichages : 3721

Catégorie : 1901 : DEFI N°11

COLUMBIA L'EMPORTE DE JUSTESSE

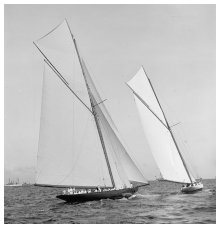

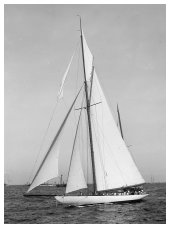

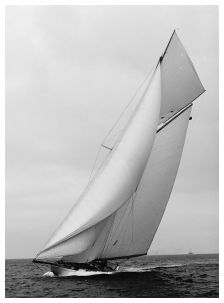

COLUMBIA L'EMPORTE DE JUSTESSE Sept. 29, 1901 - Columbia defeated Shamrock yesterday in the first of the races for the America's Cup in the finest light-weather contest ...

Sept. 29, 1901 - Columbia defeated Shamrock yesterday in the first of the races for the America's Cup in the finest light-weather contest ...

... in the history of the blue ribbon of the sea. It was a battle royal from start to finish, and while the challenger lost, she covered herself with glory by leading the defender in the fifteen-mile beat to windward.

THE RACE IN DETAIL

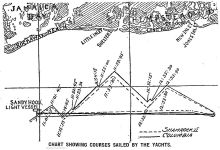

THE RACE IN DETAILWhen the Regatta Committee's boat, the big tug Navigator, arrived at the starting point, she hoisted the international code letter C, which signified that the race would be fifteen miles to windward or leeward and return. As the wind was out or the east, there was no doubt that the racers would be sent off on the windward leg of their fight first. When the signal was set the wind was light. The sky in the south and east was grayish with the fog which was setting up before the breeze. The swell was running in from the southeast, the usual set of the swell around the lightship. It was a long broad swell, neither high nor steep. The surface of the sea was quite smooth.

The tide was in the third quarter of the ebb, and the wind ad just sufficient force to throw a lively ripple on the tops of the swells, with an occasional sparkle up to windward, that showed just the suspicion of a whitecap. At 10:20 Columbia cast off her tow line, and, breaking out jib and staysail, began cruising about under her own motive power. Just three minutes later Shamrock followed suit. At 10:30 the committee boat broke out the international code letters D C G, meaning that the course was to be east by south. The Navigator now anchored 600 yards south by west of the lightship, thus forming a starting line of generous width.

The tide was in the third quarter of the ebb, and the wind ad just sufficient force to throw a lively ripple on the tops of the swells, with an occasional sparkle up to windward, that showed just the suspicion of a whitecap. At 10:20 Columbia cast off her tow line, and, breaking out jib and staysail, began cruising about under her own motive power. Just three minutes later Shamrock followed suit. At 10:30 the committee boat broke out the international code letters D C G, meaning that the course was to be east by south. The Navigator now anchored 600 yards south by west of the lightship, thus forming a starting line of generous width.

As the yachts cruised around, it was seen that Columbia had two battens in the leach of her staysail and one in her jib. Shamrock had three battens in her jib and the same number in her mainsail. The Shamrock's mainsail puckered a good deal at both clew and throat, and Columbia's looked the smoother of the two.

Under mainsails, club topsails, jibs, and staysails the racers were circling around the Navigator, which held the weather end of the line, when at 10:45 the preparatory signal was given. Now began the jockeying for the start. Both yachts ran off from the line with their sheets aft. Columbia hauled her wind and went about. She was the further of the two from the line, and she crossed Shamrock’s bows. Shamrock hoisted her baby jibtopsail and continued running off.  Columbia, going in the opposite direction, passed to windward of her. Opposite the Navigator Columbia sent up her baby jibtopsail in stops. Shamrock hauled her wind and tacked a quarter of a mile south of the committee boat. Columbia bore away around the boat at the same time. After doing this she stood along the line toward the lightship. She hauled up around the lightship and went on the port, tack. Shamrock passed under the Navigator's stern and sailed along the line to the lightship. Columbia bore away and sailed along the front of the line. As she neared Shamrock she luffed out and went on the starboard tack. At the same instant Shamrock took the port tack just south of the lightship.

Columbia, going in the opposite direction, passed to windward of her. Opposite the Navigator Columbia sent up her baby jibtopsail in stops. Shamrock hauled her wind and tacked a quarter of a mile south of the committee boat. Columbia bore away around the boat at the same time. After doing this she stood along the line toward the lightship. She hauled up around the lightship and went on the port, tack. Shamrock passed under the Navigator's stern and sailed along the line to the lightship. Columbia bore away and sailed along the front of the line. As she neared Shamrock she luffed out and went on the starboard tack. At the same instant Shamrock took the port tack just south of the lightship.

Columbia now bore away and gybed astern of Shamrock. Both were on the port tack, Columbia astern of Shamrock. Both were pretty free, but Shamrock hauled sharp up on are same tack in front of the line. Then she wore round across Columbia's bows. At this moment, 10:55, the warning signal was given, and Columbia wore round and headed back toward the Navigator. Both were now running off with sheets aft, Columbia holding the weather berth. She now broke out her baby jibtopsail. After passing the stern of the committee boat, Columbia ran off, and then luffed up again around the stern of the Navigator. Shamrock followed her. Both were now on the port tack, Columbia ahead. Columbia went on the starboard tack about 300 yards south of the lightship. Shamrock followed her.

Both now bore away, Shamrock ahead, and pointed for the stern of the Navigator. Columbia was a little higher than Shamrock and going faster. The consequence was that she arrived at the line too soon. She bore away toward Shamrock, but, being ahead of her, crossed her bows, the result being that Shamrock luffed out across her stern and took the weather berth. At this critical instant the starting signal was given, and Shamrock sped across the line in the smoke of the whistle.

Both now bore away, Shamrock ahead, and pointed for the stern of the Navigator. Columbia was a little higher than Shamrock and going faster. The consequence was that she arrived at the line too soon. She bore away toward Shamrock, but, being ahead of her, crossed her bows, the result being that Shamrock luffed out across her stern and took the weather berth. At this critical instant the starting signal was given, and Shamrock sped across the line in the smoke of the whistle.

Columbia tried to luff out on Shamrock’s weather quarter, but could not do so. But she was bothering Shamrock by being so close to her, and so Shamrock went on the port tack at 11:01:15. Columbia followed at 11:01:45. They had crossed the line two seconds apart, Shamrock at 11:00:14 and Columbia at 11:00:16, and they were now fairly off on their journey. On the port tack their both pointed equally well and showed about the same angle of heel. They made excellent weather in the easy sea, and it was clear that they were going to have a great race, barring accidents.

Shamrock was sufficiently far ahead of Columbia to break the wind for the latter, and so at 11:14:45 Capt. Barr put Columbia on the starboard tack to get her wind clear. Shamrock followed suit at 11:15:15. Shamrock was now in the weather berth, but a little astern. The wind was better, and both yachts were footing fast. On this tack they had the swell on the starboard beam, while on the port tack they haul it almost ahead. It was noticed throughout the battle that the latter condition, for some reason, seemed to suit Shamrock better.

Shamrock was sufficiently far ahead of Columbia to break the wind for the latter, and so at 11:14:45 Capt. Barr put Columbia on the starboard tack to get her wind clear. Shamrock followed suit at 11:15:15. Shamrock was now in the weather berth, but a little astern. The wind was better, and both yachts were footing fast. On this tack they had the swell on the starboard beam, while on the port tack they haul it almost ahead. It was noticed throughout the battle that the latter condition, for some reason, seemed to suit Shamrock better.

At 11:22:45 it occurred to Barr that he was too far away from Shamrock, and he put Columbia on the port tack. If he intended to cross Shamrock‘s bow he was unable to do so, and at 11:23:30 he went on the starboard tack again. It is more than likely, however, that the move was for the purpose of getting close enough to Shamrock to backwind her. The move was not successful, for Shamrock bore down on Columbia, and thus, being ramped off, sailed right up on Columbia's weather. The American yacht was now right under the other’s lee. The two were heading toward Jones's Inlet on the Long Island shore, nearly ten miles away. Shamrock's berth appeared to be higher than it was on the first starboard tack, and she was going through the water quite as fast as Columbia. The wind was all the time strengthening, and the sea was smoother than it had been in the immediate vicinity of the lightship.

Barr now gave Columbia a good full to run out from under Shamrock's lee. At 11:50, off Long Beach, Columbia was a quarter of a mile ahead, but a considerable distance to leeward. Now Barr repeated his former tactics. At 11:54:15 Columbia went on the port tack and stood toward Shamrock. Once again the spectators seemed to hold their breath in their anxiety. They naturally believed that the wily skipper of Columbia knew he was far enough ahead to cross Shamrock’s bows; but they could see that it was going to be a very close thing. Down toward the golden yacht the white American beauty sped, and with hope helping the eyesight it certainly looked from a little distance as if she would run across the challenger's bows and put Shamrock under her lee. Once there, she would be a beaten yacht.

Barr now gave Columbia a good full to run out from under Shamrock's lee. At 11:50, off Long Beach, Columbia was a quarter of a mile ahead, but a considerable distance to leeward. Now Barr repeated his former tactics. At 11:54:15 Columbia went on the port tack and stood toward Shamrock. Once again the spectators seemed to hold their breath in their anxiety. They naturally believed that the wily skipper of Columbia knew he was far enough ahead to cross Shamrock’s bows; but they could see that it was going to be a very close thing. Down toward the golden yacht the white American beauty sped, and with hope helping the eyesight it certainly looked from a little distance as if she would run across the challenger's bows and put Shamrock under her lee. Once there, she would be a beaten yacht.

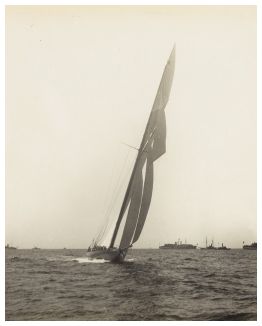

As they came together it was seen that Shamrock had an overlap on Columbia and, being on the starboard tack, had the right of way. Consequently Columbia had to tack. She went on the starboard tack at 11:55, and again looked to be in a position to backwind the challenger. But the truth was that she was under Shamrock’s lee again. Those who were a short distance to leeward of the two racers saw a significant sight not to be forgotten. The sun was away up on the weather side of the yachts, and it threw the shadow of Shamrock’s club topsail on the mainsail of Columbia, and this shadow executed a grave and stately march along the defender's great white driver. It shifted slowly forward from the clew of the sail to the bunt, and showed Shamrock was steadily gaining on this tack. There were no whistles of salute for Shamrock when Columbia failed to cross her bows, and this slow, deadly gain was watched also in dismal silence.

As they came together it was seen that Shamrock had an overlap on Columbia and, being on the starboard tack, had the right of way. Consequently Columbia had to tack. She went on the starboard tack at 11:55, and again looked to be in a position to backwind the challenger. But the truth was that she was under Shamrock’s lee again. Those who were a short distance to leeward of the two racers saw a significant sight not to be forgotten. The sun was away up on the weather side of the yachts, and it threw the shadow of Shamrock’s club topsail on the mainsail of Columbia, and this shadow executed a grave and stately march along the defender's great white driver. It shifted slowly forward from the clew of the sail to the bunt, and showed Shamrock was steadily gaining on this tack. There were no whistles of salute for Shamrock when Columbia failed to cross her bows, and this slow, deadly gain was watched also in dismal silence.

Now, for a few moments, the grim shadow seemed to fall back. Was Columbia in some mysterious way suddenly gaining? No, not exactly. Barr was again ramping her off to get her from under the lee of the merciless Shamrock. So close was Columbia to Shamrock when Barr pointed the stern of the white yacht at her foe that the latter received some of the back draught from Columbia's sails. This was not the sort of wind that Sycamore wished for, so he threw Shamrock to the port tack. Columbia held on long enough to get a berth a little more to windward than her opponent, and then at 11:59:45, or fifteen seconds later than Shamrock, she also went on the port tack. The two yachts were now about off the Long Beach Hotel, and were heading out toward the coast of Africa. Columbia was in the windward berth, but astern.

Now, for a few moments, the grim shadow seemed to fall back. Was Columbia in some mysterious way suddenly gaining? No, not exactly. Barr was again ramping her off to get her from under the lee of the merciless Shamrock. So close was Columbia to Shamrock when Barr pointed the stern of the white yacht at her foe that the latter received some of the back draught from Columbia's sails. This was not the sort of wind that Sycamore wished for, so he threw Shamrock to the port tack. Columbia held on long enough to get a berth a little more to windward than her opponent, and then at 11:59:45, or fifteen seconds later than Shamrock, she also went on the port tack. The two yachts were now about off the Long Beach Hotel, and were heading out toward the coast of Africa. Columbia was in the windward berth, but astern.

Capt. Sycamore now tried the experiment of squeezing Shamrock just a little in the hope that she might be able to eat out to windward far enough to bring Columbia directly into her wake. But this was asking more of the boat than she could do. Both skippers were taking advantage of every puff in the wind, and it was a study in skill at the helm to see them luffing and filling their yachts as the wind favored or did not favor them. Heading into the sea as they now were they were both throwing huge clouds of spray from under their bows, but it was impossible to discern that one made any better work of butting into the head sea at this time than the other.

As they reached out from the Long Island shore the seas became longer and deeper, and both yachts pitched gently as they drove out toward deep water. Here for a time the lift of the sea seemed to favor Columbia, for she gradually drew up till she was almost on the weather beam of Shamrock. The wind now for a short time showed an inclination to become more southerly, and the yachts headed half a point or so more to the south than they had on their earlier port tacks. But this turn of the wind did not last long, and it may be said that on the whole the breeze was a true one.

Columbia could not lift herself far enough up on Shamrock's weather beam to suit Capt. Barr, and at 12:32:35 he put her on the starboard tack. Shamrock followed at 12:33:50, holding the port tack long enough to lift her berth a little more to windward.

Columbia could not lift herself far enough up on Shamrock's weather beam to suit Capt. Barr, and at 12:32:35 he put her on the starboard tack. Shamrock followed at 12:33:50, holding the port tack long enough to lift her berth a little more to windward.

At 12:33:55 Capt. Barr put Columbia on the port tack once again and stood down toward Shamrock. It was a repetition of his former tactics, but again the spectators saw in it an attempt to cross Shamrock’s bows, and perhaps it was. But as such it was not successful any more than the other ones had been. Columbia dashed up to her rival only to be forced about once more by the inexorable rules of the road. Shamrock was on the starboard tack and had the right of way. Columbia could not cross her bows, and so tacked close under her weather bow and gave her a great outpouring of backwind. This tack was made at 12:35:30.

Now Capt. Barr tried to squeeze Columbia out across Shamrocks bow, but this, too, was a failure. The yachts looked to be close enough together to let a man toss the familiar sea biscuit from one to the other, but they were probably not quite so close together as that. Nevertheless, they were so near one another that the leeward yacht worried the weather one with the back draughts from her canvas, and so at 12:53:20 Capt. Sycamore, seeing that he was in a position to make the mark by a little smart work, put Shamrock on the port tack for the last time. Naturally, Columbia did not stand on the starboard tack a second longer than she had to, for she, too, was able to squeeze up around the outer mark. So at 12:53:40 Capt. Barr threw her to the port tack. Both yachts were now standing on their last board, with the mark boat not three miles away. The wind softened for a few minutes, and Columbia seemed to gain a little, but Capt. Sycamore now showed how to do a neat trick.

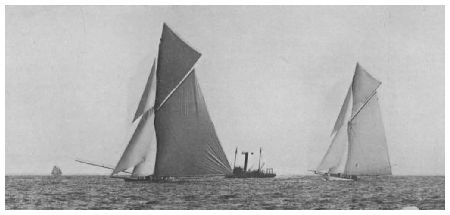

SHAMROCK AT THE OUTER MARK.

SHAMROCK AT THE OUTER MARK.He began to sail Shamrock extremely close to the wind. Of course Columbia had to pinch up a little, too. Shamrock was literally forcing her to windward of her course. The defender could not tack, for if she had done so she would have taken an unnecessary hitch, when she was able to weather the mark without it. But as Shamrock hauled up across her bow, Columbia received the challengers back wind so much that it materially deadened her way. When he had accomplished this and had approached near enough to the mark, Capt. Sycamore suddenly rolled up the helm of Shamrock and let her ramp off, which she did like a shot out of a gun. In a few moments she had jumped twice her own length away from Columbia, and with this added to her previous lead, she swept past the outer mark. It was a splendid exhibition of racing seamanship.

Shamrock was timed around the outer mark at 1:25:12 and Columbia at 1:25:53. Shamrock was 41 seconds ahead, having gained on the beat out 39 seconds. The excursion fleet seemed somewhat slow to recover from the shock of the situation, and it was not till Columbia was close to the mark that the hoarse rumble of a hundred whistles told that Americans knew how to honor a gallant rival.

Shamrock was timed around the outer mark at 1:25:12 and Columbia at 1:25:53. Shamrock was 41 seconds ahead, having gained on the beat out 39 seconds. The excursion fleet seemed somewhat slow to recover from the shock of the situation, and it was not till Columbia was close to the mark that the hoarse rumble of a hundred whistles told that Americans knew how to honor a gallant rival.

The moment Capt. Barr had Columbia around the outer mark he set to work to luff out to get Shamrock’s wind, but Capt. Sycamore would not stand any such performance. He, too, luffed, and both yachts headed right up toward the northerly wing of the excursion fleet till it looked as if a square mile of rolling yachts and revenue cutters and steamboats would be right in the way. It turned out in the end that the only vessel really near enough to the yachts to trouble them was Sir Thomas Lipton's own yacht, the Erin. But she was speedily removed.

Shamrock had her spinnaker boom down and the sail up in stops at 1:27:45, just 2 minutes and 33 seconds after rounding the mark. Columbia was ready with hers at almost the same time. At 1:30 Columbia made a feint of squaring away for the run home, and Capt. Barr cunningly broke out one stop of his spinnaker in an effort to draw Capt. Sycamore into breaking his out, in which case Barr would have luffed across his stern and broken Shamrocks wind. But Sycamore was not to be caught napping. He broke two stops of his spinnaker and then caused his men to leave off hauling on the sheet. As Barr luffed againn Sycamore was ready for him and luffed too. And so the great bluff of the spinnaker failed to work.

Shamrock had her spinnaker boom down and the sail up in stops at 1:27:45, just 2 minutes and 33 seconds after rounding the mark. Columbia was ready with hers at almost the same time. At 1:30 Columbia made a feint of squaring away for the run home, and Capt. Barr cunningly broke out one stop of his spinnaker in an effort to draw Capt. Sycamore into breaking his out, in which case Barr would have luffed across his stern and broken Shamrocks wind. But Sycamore was not to be caught napping. He broke two stops of his spinnaker and then caused his men to leave off hauling on the sheet. As Barr luffed againn Sycamore was ready for him and luffed too. And so the great bluff of the spinnaker failed to work.

At 1:31 Columbia gave it up, and, squaring away for home, broke out her spinnaker to the head. Sycamore followed suit, though he had some trouble in getting the last two or three upper stops of his sail to give way. He had to send a man to the masthead to break them by a pull on the leach of the spinnaker. At 1:33:25 Shamrock took in her little jib topsail which she had kept up for the luffing match, and Columbia followed suit at 1:33:30. Columbia broke out her balloon jib topsail at 1:35:50. Shamrock took in her staysail and broke out her balloon jibtopsail at 1:36:50.

And now began the final shift in this panoramic yacht race, the shift which was to land the victory.  To the amazement of every spectator who knew anything about yachting Columbia, in spite of her smaller sail area, began to draw up toward Shamrock, and at 1:46 was on even terms with her. At 1:48 she had drawn ahead. She had her crew all around her mast, while Shamrocks were all aft near the taffrail. This showed that the two yachts needed different trims in running before the wind. Both were rolling considerably in the sea, which was now on their port beams, and after a time Capt. Barr stationed all his crew along the starboard rail to keep Columbia's boom out of the sea, in which it, as well as Shamrock's, was occasionally dipping.

To the amazement of every spectator who knew anything about yachting Columbia, in spite of her smaller sail area, began to draw up toward Shamrock, and at 1:46 was on even terms with her. At 1:48 she had drawn ahead. She had her crew all around her mast, while Shamrocks were all aft near the taffrail. This showed that the two yachts needed different trims in running before the wind. Both were rolling considerably in the sea, which was now on their port beams, and after a time Capt. Barr stationed all his crew along the starboard rail to keep Columbia's boom out of the sea, in which it, as well as Shamrock's, was occasionally dipping.

Shamrock gained a little now, but the gain lasted only a few minutes. Barr trimmed his ballast by calling a few men aft, and then Columbia began to move faster. Shamrock at once began to drop astern, and in a very few moments there was as much open water between them as there had been when Columbia first went ahead. At 2:30 the yachts were off the Long Beach Hotel, and each was holding her own. Try as he might by holding a course directly astern of Columbia. Capt. Sycamore could not draw up to her with his gold boat. It was a foregone conclusion that Columbia would win.

Shamrock gained a little now, but the gain lasted only a few minutes. Barr trimmed his ballast by calling a few men aft, and then Columbia began to move faster. Shamrock at once began to drop astern, and in a very few moments there was as much open water between them as there had been when Columbia first went ahead. At 2:30 the yachts were off the Long Beach Hotel, and each was holding her own. Try as he might by holding a course directly astern of Columbia. Capt. Sycamore could not draw up to her with his gold boat. It was a foregone conclusion that Columbia would win.

With each yacht holding her own and no more, not a trifle of gain after the ones noted, they sailed majestically down the long lane of heaving waters between the two columns of excursion steamers, Columbia leading the way and Shamrock following at a distance of 150 to 200 yards. And thus they crossed the finish line.

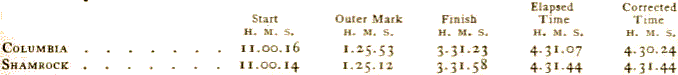

Columbia beat Shamrock in actual time over the course 37 seconds and by corrected time 1 minute 20 seconds.

On the beat to windward Shamrock occupied 2 hours 24 minutes 58 seconds and Columbia 2 hours 25 minutes 37 seconds; Shamrock’s gain, 39 seconds.

On the run home Shamrock occupied 2 hours 6 minutes 46 seconds and Columbia 2 hours 5 minutes 30 seconds; Columbia's gain, 1 minute 16 seconds.