There was something refreshing in the cool northwesterly breeze that came drifting over the upper bay in the early morning, dragging the water into the semblance of a broad tide riffle, and here and there tearing open the roughened surface to let the milk-white foam gush out, sparkling in the sunlight. The great breadths of hazy gray clouds overhead were feathery and frayed on the edges. The hills of Staten Island seemed blue with smoke, with now and then a ray of flame darting out where some cottage window reflected the sun. The tail office buildings and spires of the city towered up in a fog of coal smoke and steam; but for the first morning of this series of yacht races there was no fog on the water. The yachtsmen who had come down to the Battery to take tugs and steamers for the Scotland Lightship were charmed with the prospect and talked cheerfully, though some of the older and more weather-wise shook their heads doubtfully, fearing that a westerly breeze at this season could not last. But it was so perfect a day, from an excursionist’s point of view, that no one could long resist its cheering influence. There was something refreshing in the cool northwesterly breeze that came drifting over the upper bay in the early morning, dragging the water into the semblance of a broad tide riffle, and here and there tearing open the roughened surface to let the milk-white foam gush out, sparkling in the sunlight. The great breadths of hazy gray clouds overhead were feathery and frayed on the edges. The hills of Staten Island seemed blue with smoke, with now and then a ray of flame darting out where some cottage window reflected the sun. The tail office buildings and spires of the city towered up in a fog of coal smoke and steam; but for the first morning of this series of yacht races there was no fog on the water. The yachtsmen who had come down to the Battery to take tugs and steamers for the Scotland Lightship were charmed with the prospect and talked cheerfully, though some of the older and more weather-wise shook their heads doubtfully, fearing that a westerly breeze at this season could not last. But it was so perfect a day, from an excursionist’s point of view, that no one could long resist its cheering influence.

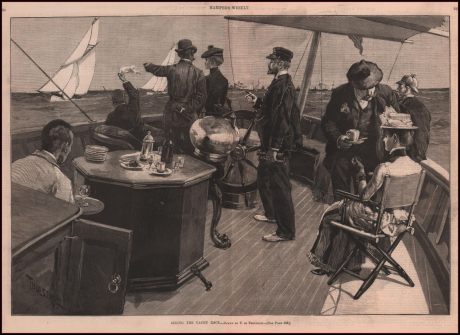

Sailors and yachtsmen alike on the pleasure fleet at Bay Ridge stepped about the deck with livelier motions than had been their custom on former race days.

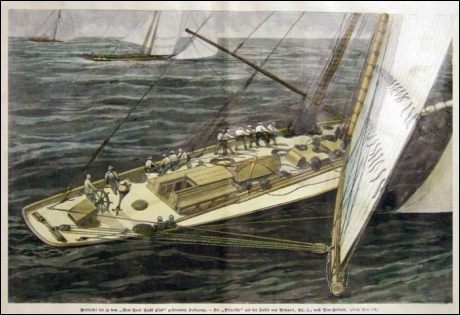

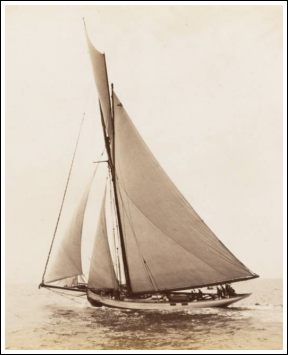

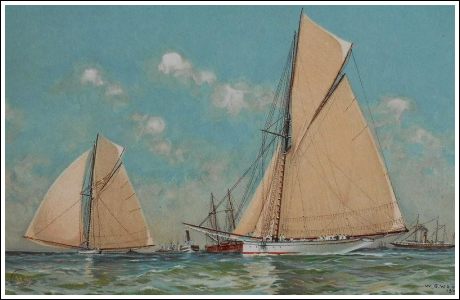

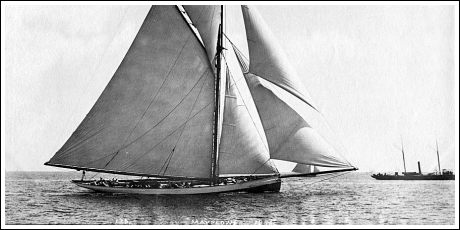

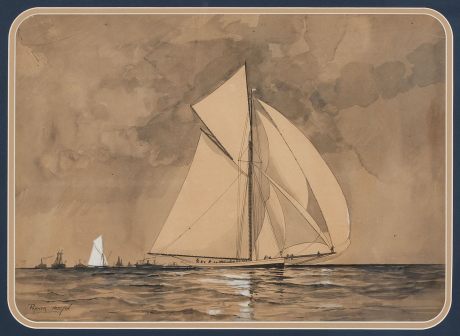

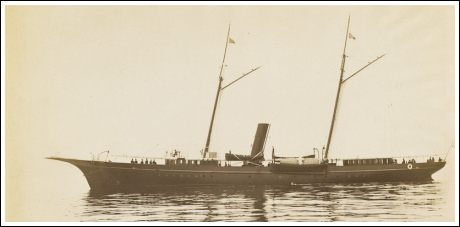

When the committees tug, the Luckenbach, arrived from the city, cables were slipped and tow lines taken on board expeditiously, and by 8:40 o’clock the graceful Mayflower in tow of the tug Scandinavian was out of the ruck of the fleet and outward bound, while the stately Galatea behind the Luckenbach was following her. The Galatea had her jib up in stops. It was the big jib and there was no reef in her bowsprit. After Thursday’s experience there was not likely to be any more reefing done on that stick, blow high or blow low.

Only two tugs and one steam yacht went around to carry the racers through the Narrows. It was a pretty early hour for most of the yachtsmen but the promise of one weather was so strong that no one doubted that there would be spectators enough at the start.

In the lower bay the tugs with the yachts in tow headed through the Swash channel, the northwest wind freshening encouragingly. A fleet of merchant vessels that could be seen outside, wing and wing, seemed to be going along bravely. The long green swells that lazily rolled in from the sea were covered with fretful white capped waves that wanted to go the other way. The land looked blue and smoky while the wind seemed to be gathering the western clouds into a white roll overhead, leaving a cloud bank below, which betokened more wind. The wind did increase to a smart capful when the tugs, after rounding the point of the Hook were passing the wreck of the dredge Queen, sunk during the fog after Thursday’s race.

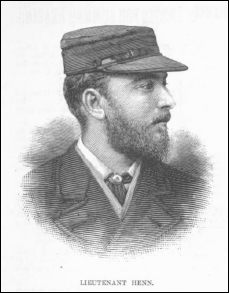

LIEUT. HENN SAILS SICK ABED.

At this point the head of the Mayflower’s jib began to show above the bowsprit, and when that sail was set the stay sail came up. Then the Galatea’s sailors swarmed, British fashion, up the rigging to ride the halyard of the big mainsail. Near the Scotland Lightship, from which the start was to be made, the Mayflower got up her mainsail, and, casting off from the tug, headed toward the Jersey shore on the starboard tack. The wind was still from the northwest. The Galatea cast off a little later from the Luckenbach, and as she came alongside Loyd Phoenix shouted to the committee: “Lieut. Henn is not very well, and asks if the course can be laid fifteen miles instead of twenty?” The Galatea cast off a little later from the Luckenbach, and as she came alongside Loyd Phoenix shouted to the committee: “Lieut. Henn is not very well, and asks if the course can be laid fifteen miles instead of twenty?”

“It is a question whether we can do that or not. Lieut. Henn wants it done, does he?” shouted back Mr. Robinson.

“Yes. He wants to get back in time to see a doctor to-night. He has caught a cold and is in his berth abed.”

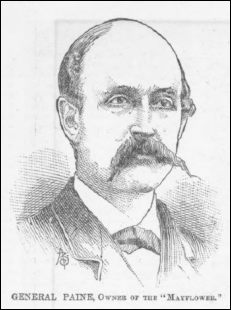

Mr. Robinson said he would consult with the committee and Gen. Paine and see what could be done. The American Cup Committee told Mr. Robinson on Thursday that the Regatta Committee could not change any of the courses.

The Luckenbach steamed over to the Mayflower and consulted Gen. Paine. He said he would express no opinion. It was a matter for the committee. The committee decided that the course could not be changed.

The Galatea made for the Jersey shore and jibed around and headed off shore on the port tack with one jib set. Both the boats got their club topsail together. It was then about 10¼ o’clock.

The excursion fleet began to arrive. The New York Yacht Club on the Taurus came along. Half a dozen steam yachts and as many tugs, all with bright colored hunting were rolling in the swells.

The pride of Staten Island, the big Priscilla, with all plain sail set, reached about with canvas seemingly as stiff as the iron hull beneath it, while trothing water curled away from her black shoulders and trailed away in her wake like a bridal veil from the head of some black princess. There wasn’t a New Yorker among the excursionists who didn’t admire her, whatever the haughty people from Boston may have said or thought. A dozen schooners and sloops would fain imitated her, but some of them were fearful of accidents aloft, and so carried reefed canvas, while the rest, with everything drawing, had to give up the task. The Priscilla’s skipper was game to try the Galatea in leeward work, as he had done to windward on Thursday, and with only a working topsail set she eventually ran away from the Briton.

A LOVELY WIND LOST BY DELAY.

To the yachtsmen not on the committee’s tug it seemed that at least half an hour was needlessly thrown away at the lightship before the tug Scandinavian was send away on her course to set the turning buoy, and the lost time was a deplorable waste of wind. Although the boats reached the lightship at 10 o’clock the buoy tug did not get her course and departure until 40 minutes later. Club measurer Hyslop, it appears, has not been informed that an earlier start than usual was contemplated and had missed the boat and came down on the Taurus. It took about 15 minutes to transfer him from the Taurus to the Scandinavian.

It seemed likely that the racers would real off the course before the wind, at ten knots or more an hour, and it was therefore necessary to give the buoy tug at least half an hour’s start. The wind being northwest, the course was twenty miles away to the southeast, the yachts having to run out, and it the wind held steady to beat back. Meanwhile the big yachts cruised about, filling and backing with booms now to starboard, now to port, with jibs to windward or to leeward as it happened, but keeping pretty well to the north and west of the line running easterly from the lightship to the Luckenbach.The racers stood on the starboard tack, reaching far over toward the Jersey shore. The Mayflower made one short leg on the port tack, but quickly came back on the starboard tack again. The wind began to die out soon after the buoy had been turned and every minute it got lighter and lighter. Finally it was almost a flat calm, and the long swells shook the sails of the yachts.

The yachtsmen and spectators were aching to see the start before the weather failed for it was then beautiful. The big arch of clouds above had been driven off to the southeast leaving a wake of fleece. Off to the northwest, past the point of the Hook, the water was black with the rough flaws of wind and simply glorious with white caps, and still they had to wait idly and see it all die before the start could be made. The Galatea, with her owner evidently wondering what it all meant, cruise down to the committee boat and then away off to the south and west toward the beach where the Empire State went ashore on Thursday. She fetched up to the wind on the starboard tack in the wake of the Mayflower which was heading off to the north on the port tack, where she was apparently figuring to get over the line behind the Galatea. Then the Galatea reached through the water close past the lightship and off to the northwest or windward to the line. which was heading off to the north on the port tack, where she was apparently figuring to get over the line behind the Galatea. Then the Galatea reached through the water close past the lightship and off to the northwest or windward to the line.

The Galatea held on for a short distance and then tacked and stood off to the west on the starboard tack. Both now began to reach about for a good position, for the time for the warning blast drew near. The Mayflower being to the west of the line and heading to the north on the port tack, kept away, and then wore around again to head for Jersey, and finally got headed to the north again and off on the port tack as before Then with the Galatea heading for the shore on the starboard tack, the long warning blast was blown from the committee tug at 11:10 o’clock.

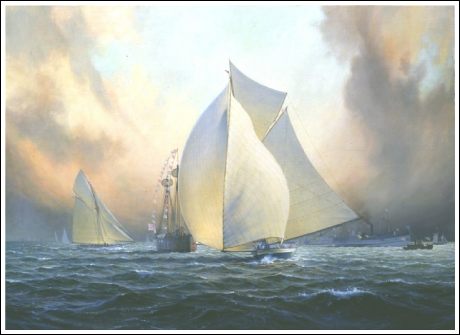

It was with a feeling akin to disgust that the spectators saw that the wind had drooped a bit, even though white caps were still as thick as snowflakes from a winter sky. The excursion fleet which now numbered about forty vessels all told, including six big side-wheelers with from 9,000 to 10,000 people on them, poured into two long ranks for the boat to sail through, most of them keeping to the east of the committee tug. Six minutes after the warning blast the Mayflower passed to the north under the Galatea’s stern. Two minutes later the Galatea eased off, heading south down the beach, which she seemed to be almost shaving, she was so far inshore while the Mayflower being on the other tack, eased off her sheet and headed for the east and then bore down toward the line. The Galatea had forced her to head for the line first. Then the Galatea wore around, and, jibing over, headed up so as to get to the north of the line for she had run well down the beach.

THE MAYFLOWER FORCED TO CROSS FIRST.

A minute before the whistle came ordering the boats to cross, the Mayflower’s boom was lowered to port. She had it on end for a long time. The big spinnaker in stop, looking like a long roll of Yankee yarn tied into banks, was hauled up and sheeted out. It burst into a bellying cloud of white a minute later, while the fleet clipper buried her clean bows in the green brine and rose again with the swell, the water dripping from the gleaming polish of the blacklead and making altogether a picture that was a delight to the eyes of the spectators. And so with everybody crowding to the sides of the boats nearest to her in order to get a better view of her stately beauty, and straining their ears for the little “toot” on the judge’s boat by which to take her time, she ploughed across, turning a narrow swath of white from either bow.

The Galatea was no less stately and beautiful as she passed across behind her, but having to reach up around the lightship she did not have so good a speed. Besides, her spinnaker burst out of stops before she got it sheeted out and she had to hold it in to the mast until she was right on the line, when she got it set cleverly. The official time of the crossing is as follows:

Mayflower 11h. 22m. 40s.

Galatea 11h. 24m. 10s.

The Mayflower was unquestionably blanketed by her opponent, which of course, followed exactly in her wake. If the Galatea was ever to outrun the sloop, then was her chance, for the excursion fleet kept a respectful distance either to the east or to the west of the procession in order not to crowd the mourners. To the great relief of something like 12,000 patriotic souls, the mourner were soon – say within twenty minutes - discovered to be on the Galatea. The sloop, in spite of the broken wind that she was getting, was able to haul away from the cutter The yachtsmen felt more like forgiving the committee for the delay at the start after that.

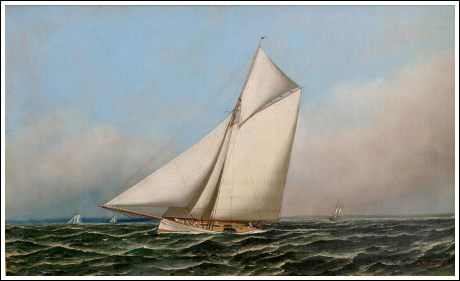

It was a genuine New York Yacht Club regatta day as noon came around. Nobody could possibly get seasick on such a day. The clouds had all been blown away off out of sight behind the haze in the southeast. The yachts in the lead and the whole fleet behind were rolling along through a broad path of reflected sunlight. The sea in other directions, with here and there a white cap, looked like a polka dot carpet of green silk. But because the wind had dropped until the yachts could make no more than eight miles an hour only the landsmen thoroughly enjoyed this part of the race. The sails of the yachts fluttered over the rollers even when crossing the line, and they fluttered more as the afternoon wore away. It was plain that there would have been no white caps at all if the northwest wind had not been rasping its way over rollers from the southeast.

A short way down the course the Priscilla bloomed out her spinnaker abreast of the Galatea and started in to make the race with the champions. The sun came out pretty hot, and one of the luxurious amateur seamen on the Mayflower’s quarter deck set the fleet to laughing by getting up an umbrella for a shade. The Mayflower had got her balloon jib on as she crossed the line but the Galatea had nothing to close the big gap above the luff of her jib and between the mast and the spinnaker until she was off Seabright, when she got up a medium jib topsail sheet to starboard, which filled at once, and in proportion to its size drew more than any sail on board. Capt. Bradford was at her tiller.

A LAZY DRIFT DOWN

The Mayflower however gained steadily, if slowly, just as she had done all along. But it was a lazy drift all the way down. A good deal of the time it looked as if there would be no race. However by 1½ o’clock, when everyone had eaten a hearty lunch and was at peace with himself and his neighbors, the buoy tug first and then the buoy itself came in sight down to the southeast, where the horizon was a clean black line, the sun having got around so far to the west the spectators no longer needed to shade their eyes when looking at the champions.

About 1:35 o’clock the Mayflower hauled down her big balloon jib. She was preparing to round the buoy which was out in the ocean15 or 20 miles east of Elberon. Ten minutes later her spinnaker was taken in. Her men worked with man-o’war precision and speed. She was then a quarter of a mile from the mark.

MAYFLOWER 15 MN. AHEAD AT THE STAKE.

The excursion fleet which was eminently respectful gathered a long way off to the south of the mark where it formed in a half moon with the hands of the skippers on the whistle ropes. With her spinnaker in, the Mayflower kept well off to the eastward so that her sails kept full and the wind, providentially it seemed, freshened once more until the little combers ran a sputter white over the lazy swells that came perhaps all the way from the Bermuda. The clipper was getting up a thrill among her worshippers then, and when she jibed over, being well to the eastward, and seemed to spurt for the buoy the devotions began - a prolonged Yankee hurrah, interrupted immediately by the sharp bang of cannon like the “amens” of enthusiastic brethren in the midst of a fervent prayer. But when the committee’s boat gave the signal announcing that she had passed the line, even the wild chorus of camp meeting song is to faint a smile for the incense of sounds that ascended to high heaven.

She had rounded the turn at 1h. 55m. 05s. The Galatea was a long way astern but the Priscilla, with sails in drawing beautifully, came up gracefully to the west of the line and rounded to the eastward getting a very cheerful greeting - almost as much, in fact as if she had been in the race. While the Mayflower reached away on the starboard tack for Long Branch, the excursion fleet waited patiently for the Galatea. She did not hold out to the eastward so far as the Mayflower had done, but jibed over sooner, and with boom well aft to port drifted down straight for the mark. A started sheet would have helped her along, but although Capt. Bradford held the tiller, she did not get the handling Just there that the yachtsmen had expected of her. She rounded very slowly at 2h. 10m. 20s. but after getting on the wind once began hunting the leader beautifully. No one could say she hove to on that tack, as had been said of her when she was sailing to windward in the fog and rain on Thursday. But the Mayflower had gained 13 minutes 45 seconds on her on the way down to the stake.

|

|

GALATEA PICKS UP A LITTLE.

For nearly an hour the wind suggested that which had raised the hopes of the yachtsmen before the start was made. It was so fresh that Mayflower, so the yachtsmen said, made the mistake of thinking she could sail faster with less canvas spread.

As the Galatea got off from the turning buoy, the Mayflower went about to the port tack when everybody had expected her to keep on well in shore in search of a breeze. While going about she got her working topsail up behind her club. She crossed the Galatea’s bow about two miles away. The excursion fleet that had formed into two long processions well off on each side of the wake of the Galatea now began to cut cross lots for the leader. The Galatea held on the starboard tack, however, and the Mayflower, in less than ten minutes, came about again, taking in her club topsail, and leaving the working topsail set at the same time.

The yachtsmen said that she had been partly influenced to do this by the example of the Priscilla, which, with working topsail only, was doing some good windward work outside, but the yachtsmen said this was a mistaken move and the result seemed to bear them out in that assertion.

CUTTER MEN BEGIN TO TALK.

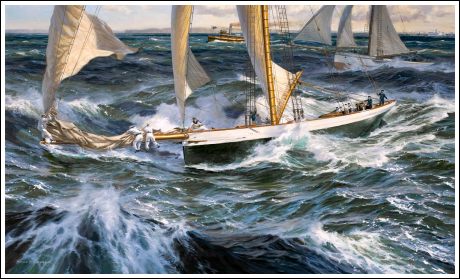

Neither boat had a jib topsail set at this time. Occasionally the Mayflower was seen to luff sharp up and then go off again. The yachtsmen called this move a North River tack because North River brick sloops sometimes manage to weather a sharp point by luffing. But it didn’t help the Mayflower to weather the cutter on that tack. The Galatea’s big lateen-like topsail was driving her upon the leader after the first half hour from the turn, and kept doing it until the cutter men gained heart, and said that it was plain that when steered by a sailor man the Galatea could weather the sloop every time she had the breeze to drive her as both yachts were then being driven. The sloop men disputed this.

Certainly it was a cutter day for a time, if ever, for the yachts were flying along at 13 miles an hour over the long swells. The sloop men contended that the tack of a club topsail was what affect the Mayflower. The fact was that while the wind held heavy the Galatea did not gain an inch but when it drooped a little, as it did before 8 o’clock and after six or seven miles of the board in had been covered, the Galatea then made quite a gain, getting up within a mile, may be, of the leader. The sloop men did not think she was as close as that. In the first hour after the Galatea turned the buoy the yachts ranged at least twelve miles in toward Long Branch.

PRETTY TO LOOK AT FROM LONG BRANCH.

It was a very beautiful race in, with the pot-lead on both boats showing far above the water on the weather side, and an instructive one to those who watched it closely and impartially. The people on shore thereafter bad a fine view of it until the boats got full down to the north on the third leg of their substantially triangular course. The sea was like a level blue floor with never a white cap to be seen.

It was not until 3:20 o’clock, when the Galatea had gained perceptibly on the Mayflower that the Yankee got their club topsail up again. They had lost the benefit of it, the yachtsmen said, during the last half hour. The Galatea met this increase of sail by getting up small flying jib. The Priscilla, which had long before tacked and followed the race, standing pretty well with the Galatea, had set the example in this move by getting up her big jib topsail, and it pulled beautifully. The Mayflower soon followed the Galatea by setting a baby jib topsail. Both boats were on the starboard tack all this time, but what there was of a wind had been canting around from the northwest, where it had held up to about 3 o’clock, until at 3:30 it was in the north and the yachts could hold a good northwest course, or well up toward the Highlands. They had headed west when they rounded the stakeboat, and at one time were broken off to west by south.

GOOD-BY TO THE RACING BREEZE.

From this time on the race became painful to the spectators who knew anything about yachting, whether they favored the sloop or the cutter model. It was a fluke, and a fluke is yachting slang for a race where shifty wind or the moon or some sort of luck decides the race. When the wind first began to drop, the steamers, in their anxiety to keep clear of the Mayflower, dropped so far off to leeward of her that they began to blanket the Galatea. It was simply inattention, for the pilots were so busy looking out for the Mayflower ahead and for one another to avoid collision that they forgot to have a look behind them. A warning blast from the Luckenbach, however, sent them flying in all directions like a flock of hens in a garden when the housewife waves her apron and shrilly shouts: “Shoo, there!” It was not long, however, until the Galatea had the sea all to herself, and if anyone was to be bothered it was the leader.

The wind at 4:05 almost in an instant shifted to the northwest, heading the Mayflower right in toward the beach. The zephyr which was barely able to fan her along so as to give her steerage way freshened so that her sails went to sleep. The Galatea did not get this flaw of wind, but she took in her baby jib topsail and set a larger one. It helped her little, for it spilled the wind every time she rolled on the swells.

JOE ELSWORTH CAPTURES ALL THE WIND THERE IS.

With but two hours and a half in which to beat up from Long Branch, it looked very much as if the Mayflower would fail to make the mark in time. The wind still heading her off, the Mayflower came about on the port tack and made about north by east at first, but later a good northerly board. The wind picked up again then and began to wrinkle and then to chafe the water. Renewed hope made the yachtsmen and spectators on the excursion fleet give the leader a good cheer, but it was not repeated partly because a second thought showed them that they were not out of the woods yet, and partly because a fluke with the Galatea becalmed far astern wasn’t anything to make even a yachtsman overbearing in his treatment of an antagonist. But the veterans on the fleet rolled their tobacco quid quietly, and, with a severe look at the land hard by, said that “It was a breeze straight from Bayonne.”

They meant by this that Capt. Joe Elsworth, in piloting the Yankee sloop, had purposely run her nose close to Jersey sand in order to catch the offshore breeze that he know would blow by and by. The Galatea got the breeze about 4½ o’clock, or nearly half an hour after the Mayflower did, and headed pretty well up but not so well as her antagonist. She was in the outer edge of the flaw, and so Capt. Bradford brought her about and made a short board in shore. She was estimated to be two miles and a half astern at the time she came about and headed north again, which was some little time before 5 o’clock. Whatever the distance, it was so great, and the sun was dropping toward the Highlands so fast, and the Scotland lightship, although in sight, was yet so far away, and the uncertainties of an offshore breeze were so well known, that the spectators forgot the cutter entirely as they watched the varying fortunes of the sloop, or remembered her merely as one remembers an engagement to be kept day after to-morrow.

They could see the long swells pound on the beach and almost hear the resounding splash and roar. Off Seabright at 5 o’clock the Mayflower got up a big jib topsail in place of the little one. A cannon near the Episcopal church on shore there boomed sullenly in her honor, first throwing a spiteful flash of fire out and then a blue cloud of smoke to mingle with the yellow Jersey dust that the wind blow out over the sea. The breeze fell and then freshened again and held the Mayflower at a six-knot rate until the Highlands killed it and let her drift at half that speed.

AGONIZING FOR A WIND.

Southeast of the Highlands, the time limit, but an hour away, and no wind. The yachtsmen paced the deck in their anxiety, and, it is feared, swore roundly when they remembered the half hour of glorious wind that was wasted in the morning. Hope fluttered faintly, and then when all but gone revived again. Another flaw had come as the Mayflower drifted clear of the horizon.

“She’ll make it now sure. No, she wouldn’t. Yes-no, she had lost it again in a greasy streak of calm, and the lightship a mile away. What a pity!”

But they couldn’t give up. The schooners and sloops that reached to and fro about the home mark had a breeze. Why shouldn’t it get down to the Mayflower? Suppose it did, it would head her off. No matter; she could make it anyhow. Then she got it again, and it didn’t head her off after all. Whoop! She’ll make it!

SHE MAKES IT.

The sun, a huge white disc with a yellow halo, was sinking slowly into a blood red mist that seemed to rise half like a sheet of flame from the black copse on the sands of Sandy Hook. The moon, round and yellow rose out of a purple cloud in the east. A path of sun light, red as gold, ran on the water from the ships to the shore, and another of moonlight, as white as silver, stretched away to the east until it was lost in the gathering night at the horizon. The blue sky overhead had darkened into green and gray. The breeze wrinkled the water until it seemed to be alive with sea sprites dancing in the silver and the gold… Into this, the Mayflower ploughed her way with quickening pace.

Beyond the line, in a huge half circle, were the excursionists piled tier on tier on the big steamers like the spectators in some monster gallery, with the little tugs and yachts on the floor of the pit, and the Mayflower, the star, bowing her way to the footlights.

THEN THERE WAS A GREAT NOISE.

Human nature could not look at that picture and keep quiet. Hats came off, handkerchiefs fluttered, and one wild cheer, beginning away down on a little tug, rolled and swelled up over the fleet into a mighty roar that shook the elements around, and might have been heard in town.

The Mayflower had crossed the line with only 11 minutes to spare and make a race of it, but she had crossed it, and the cup was safe. That was glory enough for that crowd.

The twin lights on the Highlands and the range lights on the Hook sparked out while the crowd cheered. Then came the race for home. Some of the steamers, anxious to show their speed as well as to get their patrons home early, crowded steam. One boat passed up the bay with a great flame of burning gas pouring out of its smokestack, but no damage was done to boat or person, and before 8 o’clock nearly all had been landed.

GALATEA FINISHES BY MOONLIGHT.

The Galatea was yet three miles away and was standing nearly straight, evidently having very little wind. The committee were undecided whether to go down and offer her a tow or to let her finish. They decided to wait. The lightship looked almost deserted after the huddle of a few minutes before. The John Sylvester, which had advertised to take passengers to see the finish, of course had to stay. Mr. Gerry’s Electra and the club steamer Taurus hung by so as to give the Englishman a little noise when he finished. But for these boats the Galatea would have finished by moonlight alone. She came up slowly on the same tack which she had taken off Long Branch at 4:40. As she passed over the line the Luckenbach steamed alongside to give her a line. Not a word was spoken. Neither Lieut. Henn nor his wife was on deck. Beavor-Webb stood aft, looking straight ahead, while the crew were silently drawing down the sails. The operation was as solemn as if the Luckenbach had been bitched to a hearse. When Bay Ridge was reached some one of the committee asked if the committee could do anything for Mr. Henn. Some one on the Galatea said that Mr. Henn was feeling better, and would not trouble the committee.

The official time of the race was as follows:

| |

Start. |

Finish. |

Actual

Times. |

Corrected

Times. |

| |

H. |

M. |

S. |

H. |

M. |

S. |

H. |

M. |

S. |

H. |

M. |

S. |

| Mayflower |

11 |

22 |

40 |

6 |

11 |

40 |

6 |

49 |

00 |

6 |

49 |

00 |

| Galatea |

11 |

24 |

10 |

6 |

42 |

58 |

7 |

18 |

48 |

7 |

18 |

09 |

The following show the time consumed by the yachts in going both ways, and how much the Mayflower gains each way:

| |

Lightship to

Stakebuoy. |

Stakebuoy

to Lightship. |

Total. |

| |

H. |

M. |

S. |

H. |

M. |

S. |

H. |

M. |

S. |

| Mayflower |

2 |

33 |

25 |

4 |

16 |

35 |

6 |

49 |

00 |

| Galatea |

2 |

46 |

10 |

4 |

32 |

38 |

7 |

18 |

48 |

| Mayflower's gain |

|

13 |

45 |

|

16 |

03 |

|

29 |

48 |

The following table show the times of the start and the turn, and the tacks made in sailing home:

| MAYFLOWER |

| |

|

H |

M |

S |

| |

Start |

11 |

22 |

40 |

| |

Stake |

1 |

55 |

05 |

| 1 |

Port after turn |

2 |

10 |

20 |

| 2 |

Starboard |

2 |

22 |

00 |

| 3 |

Port |

11 |

27 |

00 |

| |

Finish |

6 |

11 |

40 |

|

|

| GALATEA |

| |

|

H |

M |

S |

| |

Start |

11 |

24 |

10 |

| |

Stake |

2 |

10 |

20 |

| 1 |

Port after turn |

4 |

20 |

00 |

| 2 |

Starboard |

4 |

37 |

00 |

| 3 |

Port |

4 |

40 |

00 |

| |

Finish |

6 |

42 |

48 |

|

ABOARD THE VICTOR AND THE VANQUISHED.

The racers got to their moorings off Bay Ridge about the same time, 8 o’clock last evening. On the forecastle of the Mayflower the blue-clad sailors clustered and bargained in various shades of English with the bumboat man who supplies the yachts for various Sunday goodies. On the quarterdeck Gen. Paine and Designer Burgess rested quietly on the laurels of their boat with a more serene joy than the first race had brought them. They did not talk “shop”, but when a SUN reporter came on board were discussing orally the merits of soft-shell-crab.

Gen. Paine said he was satisfied with the result of the race but not with the race itself. Gen. Paine said he was satisfied with the result of the race but not with the race itself.

“We didn’t have the wind we wanted,” he said in his gentle voice. “Going out we had a good breeze, but coming back it was almost a dead calm. We almost stopped finally. The steamers never treated us better,” continued the slow-speaking owner of the fast-sailing Mayflower. They seemed to understand that we were fighting for time on the way up, and gave us a good show. If they hadn’t done so, we should have had no race, for there was so little wind that the slightest cross swell might have kept us back and prevented us from doing the distance in the seven hours. As it was, we just did it in time.”

Gen Paine declined to say whether he thought his boat could have beaten the Galatea in a big blow; he had been disappointed in not getting a chance to find out whether it could do so or not; that was all he would say. As to his challenge in race the Galatea in a gale from Marblehead, the General said Mr. Henn had written him a letter practically declining it. The Mayflower will remain at Bay Ridge for a day or so yet.

“From here we shall go to Boston.” said Gen. Paine. “Not at once, but in a few days, when we have got our clean clothes and some provisions on board. The boat will go out of commission as soon as she reaches Boston."

“I have no desire to take the cup to Boston’” said the General, in answer to a question. “I am a member of the New York Yacht Club, and have come on here with my boats to help that club defend the cup if it needed my assistance. The cup is in the right place, and those people who think it ought to be in Boston because it happened to be defended successfully by a Boston boat are carried away by partisanship. The cup is where it belongs.”

Mr. and Mrs. Henn, after losing a race, take the advice that Henry VIII given to Cardinal Wolsey and go to dinner with what appetite they may. They were taking the advice last evening and could not be seen by the reporters. Capt. Bradford rose out of a heap of white suited English sailors when the reporter’s boat came alongside. He seemed more cheerful than on Tuesday night as though a great strain had been taken from his mind by the finishing of the races. Mr. and Mrs. Henn, after losing a race, take the advice that Henry VIII given to Cardinal Wolsey and go to dinner with what appetite they may. They were taking the advice last evening and could not be seen by the reporters. Capt. Bradford rose out of a heap of white suited English sailors when the reporter’s boat came alongside. He seemed more cheerful than on Tuesday night as though a great strain had been taken from his mind by the finishing of the races.

“We didn’t have the wind we wanted,” said the brawny Captain, “but we’ve nothing to complain of in the way we were treated today. The steamers kept out of our way, and it was a fair race in every way, only we wish it had had another ending.”

The Captain said he understood the Galatea would remain at Bay Ridge for several days yet. Where she would go then he did not know; he supposed she would prepare for the ocean race around Bermuda.

The Electra, Commodore Gerry’s steam yacht, was brilliantly lighted up, and was the only yacht in the fleet at anchor to show more than the regulation lights. The moon gave light enough for most of the yachtsmen, and little boats with one or two people in the stern sheets glided from one dark hull to another. Everybody seemed to be glad that the Mayflower had won but nobody cared to flaunt his joy in the face of his defeated neighbor, the Galatea.

|

L'AMÉRIQUE GARDE CETTE COUPE.

L'AMÉRIQUE GARDE CETTE COUPE.