Administrator Affichages : 429

Catégorie : 1886 : DEFI N°6

PAR CHARLES E. CLAY,

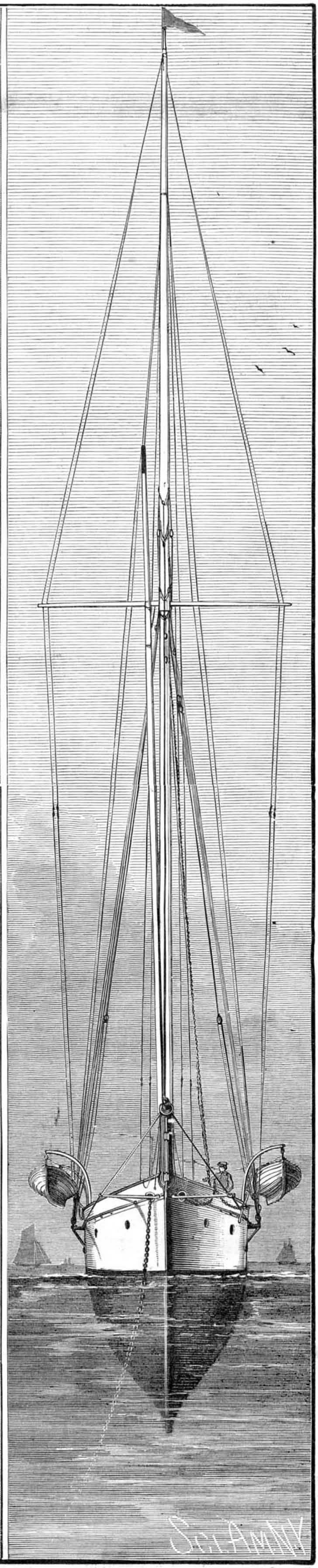

PAR CHARLES E. CLAY, If Lieutenant Henn felt enthusiastic enough to enter a competition that for the past 36 years has baffled the highest naval architectural talent of Great Britain, would it not have been more prudent to have set to work during the winter and built a yacht more after the type and model of the one that had vanquished the Genesta, built by the same designer, and embodying every principle contained in his own boat? Surely Mr. Beavor Webb is not so hopelessly wedded to his own designs and ideas as not to perceive and appreciate the good points and qualities in the productions of a rival, and a successful one at that If the results of the last two years' contests point to any conclusion at all, it is that the decided success of the American boat is not due, one iota, to the favorable condition of wind and wave, as is the universal howl of the rabid cutter men, but is inherent in the superiority of the principles involved in the construction of the model, and I con-tend most emphatically that so long as English yachtsmen go on building a V-shaped, led plank-on-end type of boat, simply because "they are so much better adapted for our waters," without ever giving the American type a fair trial, just so long will America continue to hold the yachting "blue ribbon." It is not enough for Englishmen to send one boat after another of the same type, just because each successive aspirant is claimed to be better than her predecessor. Change and modify the model from the bitter lessons that have been taught us, and then, and not till then, may we hope to compete with some reasonable prospects of victory.

If Lieutenant Henn felt enthusiastic enough to enter a competition that for the past 36 years has baffled the highest naval architectural talent of Great Britain, would it not have been more prudent to have set to work during the winter and built a yacht more after the type and model of the one that had vanquished the Genesta, built by the same designer, and embodying every principle contained in his own boat? Surely Mr. Beavor Webb is not so hopelessly wedded to his own designs and ideas as not to perceive and appreciate the good points and qualities in the productions of a rival, and a successful one at that If the results of the last two years' contests point to any conclusion at all, it is that the decided success of the American boat is not due, one iota, to the favorable condition of wind and wave, as is the universal howl of the rabid cutter men, but is inherent in the superiority of the principles involved in the construction of the model, and I con-tend most emphatically that so long as English yachtsmen go on building a V-shaped, led plank-on-end type of boat, simply because "they are so much better adapted for our waters," without ever giving the American type a fair trial, just so long will America continue to hold the yachting "blue ribbon." It is not enough for Englishmen to send one boat after another of the same type, just because each successive aspirant is claimed to be better than her predecessor. Change and modify the model from the bitter lessons that have been taught us, and then, and not till then, may we hope to compete with some reasonable prospects of victory.

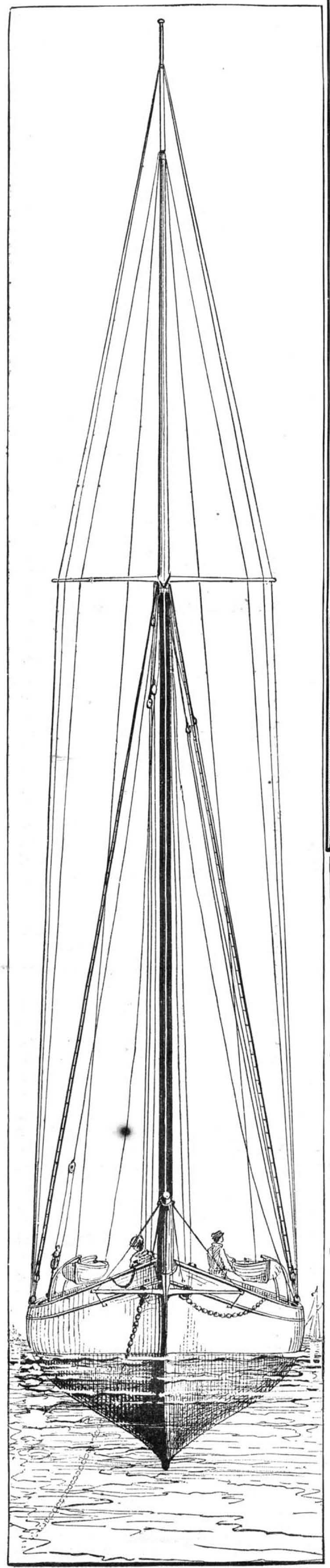

The general supposition among us in England today is that, given a gale of wind and a heavy, choppy sea, there is nothing like a deep-keeled cutter with an enormous weight of lead attached to thrash to windward. This may be undoubtedly the case with regard to the types of boats with which the majority are familiar; but it does not apply to the newest type of the American centerboard sloop, a type not known in British waters, nor to English yachtsmen; and recent trials and the most thorough tests go to prove that the Mayflower in a sea way is superior in many of the most essential qualities of a rough-weather craft; she does not bury and "hang" so long when pitching as the English model; she has a quicker recovery and rides over and not through the sea; she points up as high, and eats her way as well to windward, besides being faster.

The general supposition among us in England today is that, given a gale of wind and a heavy, choppy sea, there is nothing like a deep-keeled cutter with an enormous weight of lead attached to thrash to windward. This may be undoubtedly the case with regard to the types of boats with which the majority are familiar; but it does not apply to the newest type of the American centerboard sloop, a type not known in British waters, nor to English yachtsmen; and recent trials and the most thorough tests go to prove that the Mayflower in a sea way is superior in many of the most essential qualities of a rough-weather craft; she does not bury and "hang" so long when pitching as the English model; she has a quicker recovery and rides over and not through the sea; she points up as high, and eats her way as well to windward, besides being faster.

But I am afraid I have digressed somewhat from the object of this paper, which is to give a description of the actual incidents of the all-absorbing races, rather than a dissertation on the types and merits of the contestants.

No sooner was the challenge received than the leading clubs of the country set about seeing that nothing was left undone to retain a prize they had so long and so successfully owned. They might very naturally have said: "Well, the Galatea is no better than the Genesta; and the Puritan can do for the newcomer what she did for her sister." But that is not the spirit of the American people; they never rest content with what they have; the future is always sure to produce a better article than the best of the present. This noble spirit of emulation brought four competitors into the home lists; of them, two were old favorites; the Puritan, trusty, stanch, and bearing the laurels still fresh upon her victorious prow; the Priscilla,  with every defect altered, but still a novice eager to gain her maiden honors; the remaining debutantes were the latest skill of the builder's art; the Atlantic, which, however, never fulfilled the anticipations of her designer, and the queenly Mayflower, the fairest sea anemone that ever bloomed on American waters. All honor, then, to Boston, her birthplace, and to Mr. Burgess, her skillful designer.

with every defect altered, but still a novice eager to gain her maiden honors; the remaining debutantes were the latest skill of the builder's art; the Atlantic, which, however, never fulfilled the anticipations of her designer, and the queenly Mayflower, the fairest sea anemone that ever bloomed on American waters. All honor, then, to Boston, her birthplace, and to Mr. Burgess, her skillful designer.

The trial races were most satisfactory, and proved beyond a doubt that the Mayflower was the queen of the "big four," and to her shapely hull and tapering spars might be entrusted the glorious distinction of doing battle for her country, let come what might. To the New York Yacht Club, the oldest and leading yachting organization in this country, was entrusted with the honor of making the arrangements necessary to bring the impending struggle to a fair and impartial issue, and well did they perform their task. The gallant visitor was consulted on every point, and every concession that courtesy and Fairness could dictate, was handsomely made.

The first of the three courses to be sailed over (if three trials became necessary) was the one known as the regular New York club course, which, starting from a line off Owl's Head in the inner bay, leads out through the Narrows, rounding buoy 8½ on the port hand, and then on and around Sandy Hook lightship, and home again round buoy 8½, finishing off the Staten Island shore over a line some way to the northward of Fort Wadsworth.

This makes a splendid all-round course of 38 miles and is eminently calculated to test the various points of sailing one of the first two races, the deciding course would be a triangular one, but as it was not needed this year, the bearings need not be given.

The all-evental expectation dies, so eagerly longed for by enthusiastic thousands, dawned with anything but a promise of fine weather or favoring gales. A dull leden curtain hung over the busy city. Flags drooped limp and motionless against their poles, and with a heart full of misgivings I awaited the arrival of the Stranger at the Twenty-third Street Pier. Off in the stream lay the steam yacht Electra, while darting backwards and forwards her saucy little launch conveyed on board the guests of her owner, Elbridge T. Gerry, the commodore of the New York Yacht Club.

The all-evental expectation dies, so eagerly longed for by enthusiastic thousands, dawned with anything but a promise of fine weather or favoring gales. A dull leden curtain hung over the busy city. Flags drooped limp and motionless against their poles, and with a heart full of misgivings I awaited the arrival of the Stranger at the Twenty-third Street Pier. Off in the stream lay the steam yacht Electra, while darting backwards and forwards her saucy little launch conveyed on board the guests of her owner, Elbridge T. Gerry, the commodore of the New York Yacht Club.

Soon, down the river from Mr. Jaffray's country place on the Hudson, came the Stranger, not only one of the handsomest and largest steam yachts in the world, but certainly the fastest of its size. Our courteous host lost no time in welcoming us on board the launch; we were speedily puffed out to the larger craft, and in a few minutes more good Captain Dand was heading the Stranger full steam down stream,

"To join the glad throng that went laughing along."

We did not lack for company; every conceivable craft was bound our way, from the leviathan excursion steamers with decks massed black with people, to the tiny skiff piloted by its solitary occupant. And now we are amid the flower of America's floating palaces, and close beside us steams the Atalanta. Beyond is the Corsair, with Lord Brassey aboard. Ahead, astern, and on every side are seen the gleaming hulls of beautiful yachts, the Oriva, Orienta, Tillie, Puzzle, Radha, Magnolia, Vision, Speedwell, Ocean Gem, Theresa, Oneida, better known as the Utowana, Viking, Wanda, Nooya, Falcon, Electra, Vedette.

We did not lack for company; every conceivable craft was bound our way, from the leviathan excursion steamers with decks massed black with people, to the tiny skiff piloted by its solitary occupant. And now we are amid the flower of America's floating palaces, and close beside us steams the Atalanta. Beyond is the Corsair, with Lord Brassey aboard. Ahead, astern, and on every side are seen the gleaming hulls of beautiful yachts, the Oriva, Orienta, Tillie, Puzzle, Radha, Magnolia, Vision, Speedwell, Ocean Gem, Theresa, Oneida, better known as the Utowana, Viking, Wanda, Nooya, Falcon, Electra, Vedette.

The flyers of other days, too, are there: the Rambler, Columbia, Ambassador, Tidal Wave, Montauk, Ruth, Priscilla, Dauntless, Carlotta, Fleetwing, Mischief, Republic, Wanderer, Wave Crest, Gaviota, and a host of their fair sisters, whose names I could not get. And darting here and there among the fleet like some hissing, fiery snake, emitting from time to time the shrillest of piercing whistles, rushed the rakish-looking little steam launch Henrietta, Mr. Herreshoff's last production, said to go an average speed of 20 knots an hour.

Anxiously we scanned the distant narrows to see if there was any sign of a coming breeze, and as if, in response to the silent ejaculations of the assembled multitude, a dark ripple was seen to ruffle the glassy surface of the bay and gave the promise of a breeze outside.

It was now ten o'clock, and the rivals were daintily picking their way in and out among the waiting armada, maneuvering to get a good start as the whistle brought them across the line.

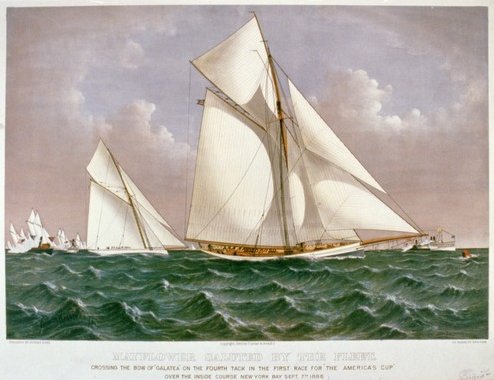

![Mayflower [and] Galatea, the start. 07 Sep 1886 - John S. Johnston 01028S2.jpg](/images/stories/1886/01028S2.jpg) At the warning scream, the Mayflower stood bravely for the line, carrying her boom to port with club-topsail, staysail, and jib set, and breaking out her jib-topsail as she crossed. Oh! it was a beautiful sight, and made every pulse beat quicker, and sent the warm blood tingling through my veins. The British cutter was not a whit behind; hauling to very sharply, she rushed, with great headway, in between the sloop and the stake boat, and got the weather gauge, blanketing her antagonist, who had to keep off a trifle in consequence.

At the warning scream, the Mayflower stood bravely for the line, carrying her boom to port with club-topsail, staysail, and jib set, and breaking out her jib-topsail as she crossed. Oh! it was a beautiful sight, and made every pulse beat quicker, and sent the warm blood tingling through my veins. The British cutter was not a whit behind; hauling to very sharply, she rushed, with great headway, in between the sloop and the stake boat, and got the weather gauge, blanketing her antagonist, who had to keep off a trifle in consequence.

This was a very smart and seamanlike maneuver, but in my humble opinion it was an error in judgment, for, had the cutter taken the leeward place, with her pace at the time, she could have stood the detriment of the blanketing for the short time they held the starboard tack, and when she went about, would have compelled the sloop to do the same, and so had the Mayflower under her lee for the long leg over to Staten Island.

However, the fact remains that, despite the Galatea's blanketing, the Boston sloop ran away from under the Englishman's lee, and when the latter, owing to her deeper draught, went about off Bay Ridge, the Mayflower stood on for another 30 seconds and came about well to windward, and had the cutter where she wanted her, and where she kept her until she was a beaten boat.

Off Fort Wadsworth, the two boats tacked again, the Mayflower at 11:13:30, and the cutter a minute later, and stood across to Fort Hamilton. Two things now quickly became apparent: that the Mayflower, though sailed a good rap full all the time, pointed just as high as the Galatea, ![Mayflower [and] Galatea, the start. 07 Sep 1886 - John S. Johnston 03688S2.jpg](/images/stories/1886/03688S2.jpg) which was evidently being sailed very fine, as shown by the continual lifting and shiver-ing of her head sails, and, that the saucy Yankee had the heels of her English rival and was creeping ahead and to wind-ward very fast. At 11.22, the Mayflower went about again, and stood on a long reach into the Narrows to get the benefit of the slackwater. Ten minutes later the Galatea tacked and stood towards the Staten Island shore, but the Mayflower had gone about again and stood towards the English-man, whom she cut about 200 yards dead to windward. While the Galatea was on this tack, the St. John, the regular Long Branch steamer, had the bad taste to sail right across the Galatea's bow, treating her to all her backwater. It was a churlish act, and showed a want of courtesy that no real "salt" would have thought of being guilty of. At 11.35 the Mayflower went about off Gravesend Bay, and the Galatea followed at the same moment, a little to the southeast of buoy No. 15. In these repeated tackings, it was noticeable that the Galatea was the handier "in stays," the American craft appearing just a trifle slug-gish.

which was evidently being sailed very fine, as shown by the continual lifting and shiver-ing of her head sails, and, that the saucy Yankee had the heels of her English rival and was creeping ahead and to wind-ward very fast. At 11.22, the Mayflower went about again, and stood on a long reach into the Narrows to get the benefit of the slackwater. Ten minutes later the Galatea tacked and stood towards the Staten Island shore, but the Mayflower had gone about again and stood towards the English-man, whom she cut about 200 yards dead to windward. While the Galatea was on this tack, the St. John, the regular Long Branch steamer, had the bad taste to sail right across the Galatea's bow, treating her to all her backwater. It was a churlish act, and showed a want of courtesy that no real "salt" would have thought of being guilty of. At 11.35 the Mayflower went about off Gravesend Bay, and the Galatea followed at the same moment, a little to the southeast of buoy No. 15. In these repeated tackings, it was noticeable that the Galatea was the handier "in stays," the American craft appearing just a trifle slug-gish.

On entering the Narrows the breeze seems to be freshening up a little, and the Yankee boat bends gracefully over to it, and the white spray dancing round her bows shows that she is quickening her pace. The Galatea stands up straighter, and is slipping through the water without much fuss, but does not seem to be gaining much on her fleet-winged rival.

Off buoy 13 the Mayflower went "in stays" again at 11.41½ and stood towards Coney Island Point, and six minutes later she was followed by the cutter. The sloop made but a short leg here, and at 11.50 she went about again, bringing both boats on the same tack, heading about east. The sloop seems to have doubled its advantage of 200 yards. They seem to be sailing the cutter a bit fuller now, but as we pass astern of her I notice that she has her weather jib-topsail sheet towing in the water. On this board the cutter appears to gain slightly on the sloop, and at half a minute before noon she goes about once more; the Mayflower follows her lead at 12.03½, and goes round between buoys 9 and 11.

Off buoy 13 the Mayflower went "in stays" again at 11.41½ and stood towards Coney Island Point, and six minutes later she was followed by the cutter. The sloop made but a short leg here, and at 11.50 she went about again, bringing both boats on the same tack, heading about east. The sloop seems to have doubled its advantage of 200 yards. They seem to be sailing the cutter a bit fuller now, but as we pass astern of her I notice that she has her weather jib-topsail sheet towing in the water. On this board the cutter appears to gain slightly on the sloop, and at half a minute before noon she goes about once more; the Mayflower follows her lead at 12.03½, and goes round between buoys 9 and 11.

The recital of tacks seems endless, but on each board the American boat in-creased her lead, and finally rounded buoy 8½ at 1:1:51, official time. The Galatea weathered the same buoy at 1:7:7. From here to buoy 5 the positions of the contest-ants did not vary much, and the Mayflower led her antagonist by about six minutes, irrespective of the 38 seconds time allowance she had to give the cutter. The wind continues light, and the sea is as smooth as a tennis court. Rounding buoy 8½ both Boats can about lie the course to the lightship, which bears S.E. by E. The breeze seems a good deal fresher outside, and the Mayflower is dancing gaily along, lying over to her plank-shear. How gloriously buoyant is her motion as she rises and falls to the gentle undulations which make up as we gain the open water! This is the longest reach of the day, and gives us all a breathing spell for refreshments.

At 2:28 the sloop comes "in stays," and takes in her jib-topsail as she stands towards the ugly-looking red hulk that shows the way into the channel. Her crew are busy getting her balloon jib-topsail run up "in stops," and soon a white streak running from truck to bowsprit end appears. The floating navy that has accompanied us all the way are gathered thickly around the lightship, hovering like bees about a sugar barrel; and now, as the swiftly gliding sloop approaches the turning-point, their pent-up enthusiasm can be restrained no longer, first one and then another impatient tug and steamer emits her shrill scream of welcome, and then all at once it seems as if every demon from the nether world is let loose, roaring around the Mayflower. The toot-toot-tooting is simply ear-splitting. Cannon thunder forth their approbation from brazen throats; frantic crowds bellow themselves hoarse; the very planks beneath my feet seem starting from the seams of the Stranger as her booming cannon, withheld by rigid discipline till the exact moment of rounding, belches forth her quota to the hurly-burly around us.

At 2:28 the sloop comes "in stays," and takes in her jib-topsail as she stands towards the ugly-looking red hulk that shows the way into the channel. Her crew are busy getting her balloon jib-topsail run up "in stops," and soon a white streak running from truck to bowsprit end appears. The floating navy that has accompanied us all the way are gathered thickly around the lightship, hovering like bees about a sugar barrel; and now, as the swiftly gliding sloop approaches the turning-point, their pent-up enthusiasm can be restrained no longer, first one and then another impatient tug and steamer emits her shrill scream of welcome, and then all at once it seems as if every demon from the nether world is let loose, roaring around the Mayflower. The toot-toot-tooting is simply ear-splitting. Cannon thunder forth their approbation from brazen throats; frantic crowds bellow themselves hoarse; the very planks beneath my feet seem starting from the seams of the Stranger as her booming cannon, withheld by rigid discipline till the exact moment of rounding, belches forth her quota to the hurly-burly around us.

But see! It is scarce five seconds since the Mayflower turned her sharp prow to plow homewards, when lo! a white puff of snowy canvas bursts like the smoke from a distant battery, and bellying to a spanking breeze, her balloon jib-topsail is sheeted home and envelops her from top-mast head to end of her jibboom, and away aft to her full waist. Well and smartly handled, ye motley crew; you may not look so neat and natty as the uniformed lads of the Galatea, but the old Norse blood of your forefathers runs in your veins, and ye are no degenerate sons of Hengist and Horsa, and the other Vikings of your native land.

But Va victis! Already the tardy cutter is almost forgotten as she struggles bravely on, irrevocably handicapped beyond redemption now, for the sloop is running while she still has a weary beat before she can do the same. At last she too tacks for the turning mark, but carries her baby jib-topsail to the very last minute, in the hope of gaining a yard or two thereby. She tacked at 2:40, and at 2:44 is fairly off after her rival. Now, boys, bear a hand; up with your balloon; you have not a moment to lose; the breeze that favored the Yankee is fast dying away, and you must make the most of it. Why, what's the matter, ye hardy sons of Yarmouth? Ah, there it goes up!-up! What! it's surely not foul? Yes! down, down, it has to come, and three weary minutes are consumed before it gets to the topmast head, and begins to draw. The game is well-nigh over now; Away in the distance, like some huge albatross with outspread pinions, the Mayflower is nearing buoy 8½, which she rounds at 3:34, and so round S.W. spit buoy 32 minutes later, and jibed her mainsail to get her spinnaker under way. But the wind had hauled into the eastward, and the boom was left in slings ready to be dropped at a moment's notice.

But Va victis! Already the tardy cutter is almost forgotten as she struggles bravely on, irrevocably handicapped beyond redemption now, for the sloop is running while she still has a weary beat before she can do the same. At last she too tacks for the turning mark, but carries her baby jib-topsail to the very last minute, in the hope of gaining a yard or two thereby. She tacked at 2:40, and at 2:44 is fairly off after her rival. Now, boys, bear a hand; up with your balloon; you have not a moment to lose; the breeze that favored the Yankee is fast dying away, and you must make the most of it. Why, what's the matter, ye hardy sons of Yarmouth? Ah, there it goes up!-up! What! it's surely not foul? Yes! down, down, it has to come, and three weary minutes are consumed before it gets to the topmast head, and begins to draw. The game is well-nigh over now; Away in the distance, like some huge albatross with outspread pinions, the Mayflower is nearing buoy 8½, which she rounds at 3:34, and so round S.W. spit buoy 32 minutes later, and jibed her mainsail to get her spinnaker under way. But the wind had hauled into the eastward, and the boom was left in slings ready to be dropped at a moment's notice.

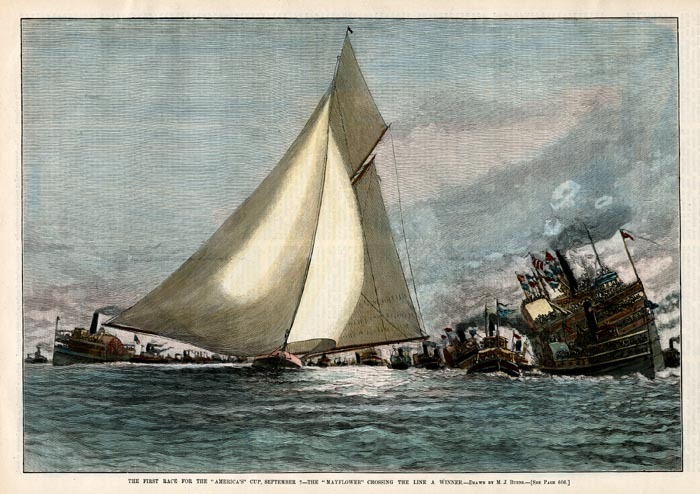

The Galatea rounds buoy 8½ at 3.46.3/4, and the SW spit buoy at 3.50. The wind freshens a trifle, and the cutter tries her spinnaker, and the Mayflower follows almost immediately. The goal is rapidly neared now; the same demonic noises commence, but are kept up twice as long, and, if it were possible, are twice as loud. The very bosom of the mighty deep seems to tremble, and, amid salvos of cannon, the jubilee of 50,000 throats, and the ovation, congratulations, and rejoicings of such a multitude as had never before gathered on New York's historic bay, the peerless Boston sloop Mayflower bore her happy owner, General Paine, over the line at 4.22½. I append the official time:

Mayflower wins by 12mn 2s

The conclusions to be drawn and the lessons taught by this momentous struggle were briefly these: that in light breezes and a smooth sea, the English model, as represented by the Genesta, Galatea, and Irex type, cannot compete at beating, reaching, or running with the American build. That with regard to seamanship and expert handling of their craft, the Americans have nothing to learn from their cousins from over the water. That, having at the outset been the humble disciples of the mother country, They have reached that stage in the science and art of yacht building and equipment that entitles the learner to usurp the position of teacher.

The following details of the dimensions of the rig and sail area of the contending yachts will be read with interest by the initiated. For the information about the Galatea, I am indebted to the courtesy of Mr. J. Beavor Webb, and the figures referring to the Mayflower were kindly furnished to me by Mr. Burgess at the request of her owner, General Paine:

As I threaded my way to the bows of the members' boat of the New York Yacht Club, on which Mr. Hurst, the treasurer, had kindly secured me a passage, I felt that I was about to witness the same performance outside the Hook that had saddened my spirits on the first day.

The weather was most unfavorable; drizzling rain commenced before we left Pier No. 1 and continued without intermission to speak of throughout the entire day. Added to these discomforts, a dense fog settled down early in the afternoon and put an end to the race and to any enjoyment of the trip, and sent us home groping our way, and landed us late, hungry, and thoroughly miserable. In discussing this abortive attempt to finish this series of races, I shall confine myself strictly to the details and technicalities of the contest, leaving the reader to supplement the accompaniments and accessories from my previous description, his vivid imagination, or the details to be gathered from the voluminous expressions of opinion in the daily press accounts. The wind had risen considerably by the time we reached the Scotland lightship, and the weather gave angry tokens of letting loose a regular sou'wester. It was manifestly a clinking "cutter's day," and right merrily did the Galatea lads move smartly about, taking a reef in the running bobstay, running in her bowsprit, hauling down the big jib, and substituting the second-sized one. Lieutenant Henn did not mean to be caught napping.

The weather was most unfavorable; drizzling rain commenced before we left Pier No. 1 and continued without intermission to speak of throughout the entire day. Added to these discomforts, a dense fog settled down early in the afternoon and put an end to the race and to any enjoyment of the trip, and sent us home groping our way, and landed us late, hungry, and thoroughly miserable. In discussing this abortive attempt to finish this series of races, I shall confine myself strictly to the details and technicalities of the contest, leaving the reader to supplement the accompaniments and accessories from my previous description, his vivid imagination, or the details to be gathered from the voluminous expressions of opinion in the daily press accounts. The wind had risen considerably by the time we reached the Scotland lightship, and the weather gave angry tokens of letting loose a regular sou'wester. It was manifestly a clinking "cutter's day," and right merrily did the Galatea lads move smartly about, taking a reef in the running bobstay, running in her bowsprit, hauling down the big jib, and substituting the second-sized one. Lieutenant Henn did not mean to be caught napping.

No change was made on the Mayflower. She carried her big jib and gained a great advantage thereby. Both craft thought it best to carry only working topsails.

At 11:20 the preparatory whistle was blown from the steam tug Luckenback, while the Scandanavian had been started ahead to mark out a 20-mile course east by north, dead in the teeth of a fresh breeze of wind that put the racing craft scuppers to and sent the black waves seething and boiling in their wake.

Almost immediately after the starting signal, the Mayflower bounded across the line, just skinning past the lightship. The Galatea was quite a good deal to leeward and had to shake up a trifle into the wind to pass the judge's boat. The times of crossing were 11:30:30 and 11:30:32. Both craft were being sailed a shade fine, but the Boston sloop evidently held her way better, while the cutter made more leeway than she ought.

Almost immediately after the starting signal, the Mayflower bounded across the line, just skinning past the lightship. The Galatea was quite a good deal to leeward and had to shake up a trifle into the wind to pass the judge's boat. The times of crossing were 11:30:30 and 11:30:32. Both craft were being sailed a shade fine, but the Boston sloop evidently held her way better, while the cutter made more leeway than she ought.

The Galatea did not relish her position and at 11:50 made her first tack, quickly followed by the sloop. It was at once apparent that the old game had commenced, and the Boston boat, like a giddy girl, was romping away from her more sedate English sister. The difference in set of the The sails of the two boats were also very noticeable, for while the Mayflower's canvas was stretched flat as a board, the leech of the Galatea kept licking about the whole way to windward and must have been as annoying to her owner as it was disheartening to the gazing cutter men.

At 12:20, the Sandy Hook lightship was passed, and the sloop had a clear lead of half a mile. The Mayflower made another short board at 12:58, returning to her original tack at 1:11. The Englishman held straight on. The wind shows a tendency to lighten, and at 1:27, the Galatea sent down her working topsail and replaced it smartly with her club-topsail.

When about half the windward course was done, the Mayflower appeared about 2.5 miles distant, dead to windward of the cutter At 1:37 the sloop tacked, and while shaking "in stays" her crew very smartly sent aloft her club-topsail to windward of her working one. The Galatea tacked again at 1:39, and apparently got a better wind, and seemed to have closed up the gap somewhat. At 1:50 the wind had lightened enough to allow the sloop to send up her jib-topsail. The sea also became smoother, and the fog began to settle down so thick that it was with difficulty the Galatea could be discerned a full three miles to leeward, which the sloop gradually widened to four or five before she rounded the mark buoy at 4:24:45 by my time. I saw nothing more of the Galatea that day, but read that she bore up for home when the Mayflower rounded. Fog, light wind, and closing darkness put an end to the race, which counted for nothing, as it was not sailed within the seven-hour limit, but it proved to the most skeptical the marked superiority of the sloop at the very game that was fondly believed to be par excellence a cutter's, for the Mayflower gained almost all her advantage while the sea and wind held. She outwinded and outspeeded the English cutter, and did not make nearly the leeway the Galatea did.

A glorious yachting day, a bright sun, and a fresh, steady breeze ushered in the final discomfiture of the cutter and her partisans. Space does not permit me to go into the details of the struggle; nor is it needed. The program for Tuesday and Thursday was enacted without a hitch. The Mayflower left the Galatea in the run to leeward, increased the lead in the thrash to windward back home, and finally won the deciding event by 29m 9s. For the subjoined history of the America's Cup, I am indebted to my friend, Captain Roland F. Coffin, famous as a sailor, and even more so as the historian of sailors' deeds:

A glorious yachting day, a bright sun, and a fresh, steady breeze ushered in the final discomfiture of the cutter and her partisans. Space does not permit me to go into the details of the struggle; nor is it needed. The program for Tuesday and Thursday was enacted without a hitch. The Mayflower left the Galatea in the run to leeward, increased the lead in the thrash to windward back home, and finally won the deciding event by 29m 9s. For the subjoined history of the America's Cup, I am indebted to my friend, Captain Roland F. Coffin, famous as a sailor, and even more so as the historian of sailors' deeds:

The cup, which has once more been successfully defended by an American yacht, was first won by the schooner America in 1851, in a race of the Royal Yacht Squadron around the Isle of Wight, she sailing as one of a large fleet of schooners and cutters. The popular impression is that she sailed against the whole fleet; but this is incorrect. She simply sailed as one of them, each one striving to win. When won, it became the property of the owners of the America and was brought by them to this country and retained in their possession for several years.

They then concluded to make it an international challenge cup and, by a deed of gift, placed it in the custody of the New York Yacht Club as trustee By this deed of gift, any foreign yacht may compete for it upon giving six months' notice and is entitled to one race over the New York Yacht Club course. There is, however, a clause in the deed which allows the challenger and the club to make any conditions they choose for the contest, and as a matter of fact, it has never been sailed for under the terms expressed in the deed of gift; the two parties have always been able to agree upon other conditions.

They then concluded to make it an international challenge cup and, by a deed of gift, placed it in the custody of the New York Yacht Club as trustee By this deed of gift, any foreign yacht may compete for it upon giving six months' notice and is entitled to one race over the New York Yacht Club course. There is, however, a clause in the deed which allows the challenger and the club to make any conditions they choose for the contest, and as a matter of fact, it has never been sailed for under the terms expressed in the deed of gift; the two parties have always been able to agree upon other conditions.

When the schooner yacht Cambria came for it in 1870, she being the first challenger, the six months' notice was waived, and she sailed against the whole fleet, against the protest of her owner, Mr. James Ashbury, he contending that only a single vessel should be matched against her. The Cambria was beaten, and Mr. Ashbury had the schooner Livonia built expressly to challenge for this cup. The matter of his protest having been referred to Mr. George L. Schuyler, the only one of the owners of the America who was living, he decided that Mr. Ashbury's interpretation of the deed of gift was correct, and that such was the intention of the donors of the cup. When the Livonia came, in 1871, the club selected four schooners, the keel boats Sappho and Dauntless, and the centerboards Palmer and Columbia, to defend the cup, claiming the right to name either of those four on the morning of each race. The series of races was seven, the best four to win. There were five races sailed, the Columbia winning two, the Sappho two, and the Livonia one.

The next challenger was the Canadian schooner Countess of Dufferin in 1876, and Major Gifford, who represented her owners, objected to the naming of more than one yacht by the New York Club and asked that she be named in advance. The New York Club has from the first behaved in the most liberal and sportsmanlike manner in relation to this cup, and on this occasion it assented to Major Gifford's request and named the schooner Madeleine. The races agreed upon were three, best two to win. Only two were sailed, Capt. "Joe" Elsworth sailing the Canadian yacht in the second race. The Madeleine won both races with ease.

In 1881, a challenge was received from the Bay of Quinte Yacht Club, naming the sloop Atalanta, and the conditions agreed upon were the same as in the race with the other Canadian yacht, the club naming the sloop Mischief, which won the first two races.

The next challenger was the cutter Genesta last year, with practically the same conditions being agreed upon as in the two previous races. The only difference was that, as a concession to the challenger, two of the three races were agreed upon to be sailed outside the Hook. The Puritan won the first two races, as the Mayflower has won them this year. From first to last, the only victory of either of the challengers was that of the Livonia over the Columbia, which was gained by the American yacht carrying away part of its steering gear.