Yves GARY Affichages : 3734

Catégorie : 1901 : DEFI N°11

SHAMROCK DEFEATED, CUP REMAINS HERE

SHAMROCK DEFEATED, CUP REMAINS HERE Oct. 5, 1901 - The third and last race of the series for the America's Cup was sailed yesterday and concluded with the most magnificent finish ...

Oct. 5, 1901 - The third and last race of the series for the America's Cup was sailed yesterday and concluded with the most magnificent finish ...

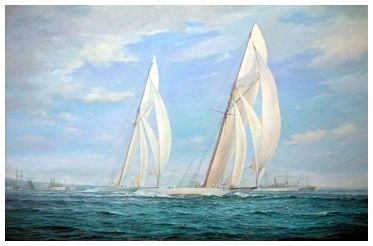

... ever seen in a yacht race in this country. After starting practically together in a run down the wind, both yachts crossing the line after the handicap gun was fired, and being timed at 11:02, they crossed the line at the finish really neck-and-neck after a hammer-and-tongs struggle of thirty miles.

THE RACE IN DETAIL (PAS DE TRADUCTION)

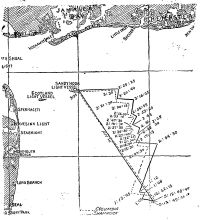

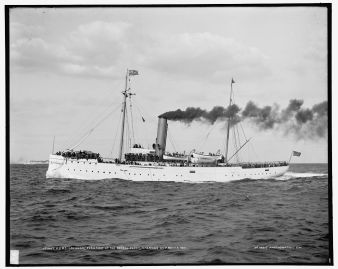

THE RACE IN DETAIL (PAS DE TRADUCTION)There was a long swell rolling in from the southeast and a little cross sea on its surface with little bunches of cottony crests. The compass course was signaled from the committee boat south by west, the code letters being D. F, G. The committee boat was anchored to the eastward of the lightship, and the Luckenbach was sent away to log the course, the guideboat in the meanwhile taking up a position about a quarter of a mile down the course.

When the Regatta Committee's boat, Navigator, arrived at the lightship the wind was north-northwest and blowing at the rate of about eight knots an hour. The sea was perfectly smooth, with an almost imperceptible swell from the southeast. The last of the flood tide was making, but it was not strong enough to tail the lightship against the wind. The Navigator anchored west-southwest of the lightship and hoisted the course signals signifying that the course was south-southeast, fifteen miles to leeward and return. The preparatory gun was fired at 10:45. At this time both yachts were cruising about under mainsails, club-topsails, and jibs. When the warning gun was fired both were to windward of the lightship, heading into the wind. Columbia was ahead and to the southward. The maneuvering for the start began with both working up to windward on the port tack.

When the warning gun was fired both were to windward of the lightship, heading into the wind. Columbia was ahead and to the southward. The maneuvering for the start began with both working up to windward on the port tack.

Columbia went on the starboard tack and then wore away, while Shamrock tilled away on the port tack and also wore around. Two minutes before the starting signal Columbia luffed up on the port tack, while Shamrock went on the port tack again and shot far up to windward. Columbia was now on the Shamrock's port beam. Shamrock tilled away on the starboard tack, Columbia imitating the move. Columbia was now ahead, with the Shamrock following her. Both were running along the line southward when the starting gun was fired.

Columbia headed for the line with sheets flat. Shamrock, astern of her, squared away, lowered her spinnaker boom to starboard, and broke out her balloon jibtopsail. A few seconds later she broke out her spinnaker. Columbia delayed the same movements till she was on the line. As she crossed she ran ahead. Both yachts, however were behind the handicap gun, Columbia by forty seconds and Shamrock by ten more. Both, therefore, were timed at starting at 11:02.

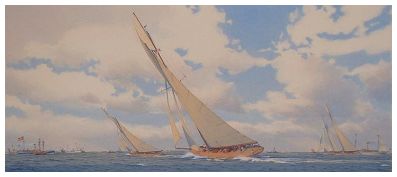

![The Start, Columbia leading, Oct. 4, 1901 [with Shamrock II at left]](/images/stories/1901/Start04oct.jpg) Columbia held the westerly berth, and maintained her position in the lead. The speed of the yachts at this time was not great, but it increased as they neared the outer mark, fifteen miles off Asbury Park. At 11:20 Shamrock's greater sail area had done it work in the growing breeze, and she passed Columbia to the eastward. The challenger was carrying her spinnaker boom guyed further forward than Columbia's, and this seemed to help her. She also had the sheet of her spinnaker hauled well in, while Columbia's was well forward. At 11:50 Shamrock had a lead of about 300 yards. The yachts were now eight miles from the lightship, and Shamrock was slowly increasing her lead. Barr was working Columbia out on Shamrock weather quarter with the intent or breaking the challenger's wind, especially if the breeze went any more to the westward. At 12:03 Columbia took a fine puff of wind and gained materially on the leader. While Columbia was making this advance Shamrock's kites were hanging all slack. She seemed to have run into a soft spot, and was rapidly losing her lead.

Columbia held the westerly berth, and maintained her position in the lead. The speed of the yachts at this time was not great, but it increased as they neared the outer mark, fifteen miles off Asbury Park. At 11:20 Shamrock's greater sail area had done it work in the growing breeze, and she passed Columbia to the eastward. The challenger was carrying her spinnaker boom guyed further forward than Columbia's, and this seemed to help her. She also had the sheet of her spinnaker hauled well in, while Columbia's was well forward. At 11:50 Shamrock had a lead of about 300 yards. The yachts were now eight miles from the lightship, and Shamrock was slowly increasing her lead. Barr was working Columbia out on Shamrock weather quarter with the intent or breaking the challenger's wind, especially if the breeze went any more to the westward. At 12:03 Columbia took a fine puff of wind and gained materially on the leader. While Columbia was making this advance Shamrock's kites were hanging all slack. She seemed to have run into a soft spot, and was rapidly losing her lead.

However, at 12:06 Shamrock began to get the favor of the wind once move and to hold her own. Her lead had been cut down one-half, and Columbia wake close enough astern to bother her.  At 12:25 the wind backed a point to the westward, coming from northwest by north, and this helped Columbia. Capt. Barr eased his spinnaker forward, and hauled aft his mainsheet a little to meet the new wind. Shamrock at 12:31 took in her balloon jibtopsail and set her, working jib and staysail. The latter sail was broken out at 12:36. Some of the upper stops refused to let go at first, and a man was sent up to break them. Then Shamrock sent up her baby jibtopsail in stops and trimmed in her mainsail.

At 12:25 the wind backed a point to the westward, coming from northwest by north, and this helped Columbia. Capt. Barr eased his spinnaker forward, and hauled aft his mainsheet a little to meet the new wind. Shamrock at 12:31 took in her balloon jibtopsail and set her, working jib and staysail. The latter sail was broken out at 12:36. Some of the upper stops refused to let go at first, and a man was sent up to break them. Then Shamrock sent up her baby jibtopsail in stops and trimmed in her mainsail.

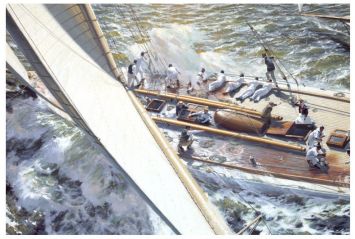

At 12:47:50 Columbia started to lower her balloon jibtopsail, and immediately she was in trouble. One of the snap hooks which attached the sail to its stay caught in the leach of the spinnaker and held the jibtopsail up. Pulling and hauling did no good except, to tear a hole in the spinnaker, and finally a man had to be sent aloft, in a boatswain’s chair to clear the tangle.  When this was accomplished the balloon jib topsail went down and the spinnaker swayed forward till it fell over the jibtopsail stay and hung in loose bags to leeward. When it finally ran down it went into the water under the lee bow, but smart work on the part of the crew soon got it on board. Columbia then broke out her jib and staysail as she headed for the outer mark. Meanwhile Shamrock had handsomely taken in her spinnaker, and, with her beating canvas drawing well stood for the mark. She had a lead of about 200 yards as she rounded, at 12:48:46. Columbia followed at 12:49:35.

When this was accomplished the balloon jib topsail went down and the spinnaker swayed forward till it fell over the jibtopsail stay and hung in loose bags to leeward. When it finally ran down it went into the water under the lee bow, but smart work on the part of the crew soon got it on board. Columbia then broke out her jib and staysail as she headed for the outer mark. Meanwhile Shamrock had handsomely taken in her spinnaker, and, with her beating canvas drawing well stood for the mark. She had a lead of about 200 yards as she rounded, at 12:48:46. Columbia followed at 12:49:35.

Shamrock luffed around the mark and hauled up on the starboard tack. Columbia luffed sharp up, went about, and took the port track at once. This was done to get her wind clear, for it she had followed the challenger she would have been too close astern or her. As soon as Columbia had stood far enough out to get the weather berth, she went on the starboard tack at 12:52:15. The two yachts were now heading west by south toward the New Jersey shore. The wind had freshened so that instead of breaking out the jib topsail which she had sent up before rounding Shamrock lowered it again.

The challenger was now showing a fine burst of speed, and seemed to be going faster than Columbia. It was at this point that the first mistake of the race was made by Shamrock. Instead of continuing on the starboard tack toward the shore and thus working into the freshening and westering wind, she went about at 1:05, and stood away to sea on the port tack. This movement enabled her to make what might be termed in baseball parlance, a grand stand play, for at 1:07 she crossed Columbia’s bows well ahead.

And now every expert in the fleet expected to see Shamrock tack on Columbia's weather bow, and having put the defender under her lee, keep her there.  But this was precisely what Shamrock did not do. She held her port tack for a good minute, going away from Columbia and out to seaward, while Columbia was rushing in toward the land and toward the better wind. At 1:08 Shamrock took the starboard tuck when she was away down on Columbia's quarter, and had literally thrown away an advantage of vital moment to herself. For four minutes she followed the defender on this tack, holding the weather berth, but being far astern, and then she went on the port tack again at 1:12. This time it looked as if her people actually thought they would find the better wind further out, or else they fancied that their yacht could go faster on the port tack. This, indeed, she did.

But this was precisely what Shamrock did not do. She held her port tack for a good minute, going away from Columbia and out to seaward, while Columbia was rushing in toward the land and toward the better wind. At 1:08 Shamrock took the starboard tuck when she was away down on Columbia's quarter, and had literally thrown away an advantage of vital moment to herself. For four minutes she followed the defender on this tack, holding the weather berth, but being far astern, and then she went on the port tack again at 1:12. This time it looked as if her people actually thought they would find the better wind further out, or else they fancied that their yacht could go faster on the port tack. This, indeed, she did.

At 1:13:05 Columbia went on the port tack. She was now away to windward, and though astern she had the better position of the two yachts. She was footing very fast. The wind began to lighten and Columbia sent men out on her bowsprit to send up the baby jibtopsail. Shamrock saw the movement and imitated it, but Columbia broke out her jibtopsail first at 1:15:45. Shamrock’s was spread at 1:16:35. Columbia was now on the weather beam of the challenger. The wind was falling lighter and was becoming a little streaky. The first result of the streakiness was that Columbia had the better slant, and was soon a half a mile up on Shamrock’s weather beam. Shamrock for a time appeared to be falling off to leeward, but as the wind became still lighter the weather grew decidedly to her liking, and she began to outfoot Columbia at a fine pace. Out to sea on a long port tack stood the two racers, Capt. Barr not daring to stand in toward the shore and leave Shamrock for it is a good rule or yacht racing to stay by the yacht one wishes to beat.

At 1:13:05 Columbia went on the port tack. She was now away to windward, and though astern she had the better position of the two yachts. She was footing very fast. The wind began to lighten and Columbia sent men out on her bowsprit to send up the baby jibtopsail. Shamrock saw the movement and imitated it, but Columbia broke out her jibtopsail first at 1:15:45. Shamrock’s was spread at 1:16:35. Columbia was now on the weather beam of the challenger. The wind was falling lighter and was becoming a little streaky. The first result of the streakiness was that Columbia had the better slant, and was soon a half a mile up on Shamrock’s weather beam. Shamrock for a time appeared to be falling off to leeward, but as the wind became still lighter the weather grew decidedly to her liking, and she began to outfoot Columbia at a fine pace. Out to sea on a long port tack stood the two racers, Capt. Barr not daring to stand in toward the shore and leave Shamrock for it is a good rule or yacht racing to stay by the yacht one wishes to beat.

At 1:55 Shamrock was closing up the stretch of open water which lay between her bowsprit and the end of Columbia’s boom as seen from a mile to windward of the two. The challenger was going admirably now, and at 2 o‘clock she had passed Columbia and showed a good space of open water between her stern and Columbia’s bow. In a few moments this space had grown to be a quarter of a mile, and then Capt. Barr thought it was time to be up an doing. So he threw Columbia to the starboard tack at 2:03:30. Shamrock held on just a minute and then followed suit.

A view from directly ahead of the racers now showed that Shamrock was holding a course half a mile more to windward than that of Columbia, but was some distance astern. There was no doubt, however, that her splendid work on the long port tack had netted her a handsome gain. And now the wind favored Columbia in an astonishing manner. She caught a slant from the original quarter. It came right across Shamrock‘s bows without touching her and lifted Columbia so that she headed a point and a half higher than her opponent. This puff lasted a minute and a half, and it set Columbia not less than 200 yards to windward. It was 2:10 when the defender got this slant of wind, and at 2:14 she received another which lasted her a quarter of a minute and gave her another nice lift.

A view from directly ahead of the racers now showed that Shamrock was holding a course half a mile more to windward than that of Columbia, but was some distance astern. There was no doubt, however, that her splendid work on the long port tack had netted her a handsome gain. And now the wind favored Columbia in an astonishing manner. She caught a slant from the original quarter. It came right across Shamrock‘s bows without touching her and lifted Columbia so that she headed a point and a half higher than her opponent. This puff lasted a minute and a half, and it set Columbia not less than 200 yards to windward. It was 2:10 when the defender got this slant of wind, and at 2:14 she received another which lasted her a quarter of a minute and gave her another nice lift.

With the benefit thus obtained Capt. Barr thought it was advisable to go on the port tack, and this he did at 2:15:30. It was evident that Barr’s aim was to rush across Shamrock's bow and tack on her weather. But as Shamrock worked over to the westward she got the benefit of a slant and headed higher, so that Columbia tell under her lee, and at 2:16:30 the challenger crossed the defender's bows. This time Capt. Sycamore lost not a trick or the game, but at once tacked at 2:16:50 on Columbia’s weather bow. This was wholly unsuitable to Capt. Barr, and at 2:17:15 he promptly threw Columbia to the starboard tack. The uncertainty of the wind was shown by the wide divergence of the courses of the two yachts as they went off on opposite tacks. They were heading about ten points apart. Shamrock seemed again to be having the worst of the struggle and to be losing ground.

With the benefit thus obtained Capt. Barr thought it was advisable to go on the port tack, and this he did at 2:15:30. It was evident that Barr’s aim was to rush across Shamrock's bow and tack on her weather. But as Shamrock worked over to the westward she got the benefit of a slant and headed higher, so that Columbia tell under her lee, and at 2:16:30 the challenger crossed the defender's bows. This time Capt. Sycamore lost not a trick or the game, but at once tacked at 2:16:50 on Columbia’s weather bow. This was wholly unsuitable to Capt. Barr, and at 2:17:15 he promptly threw Columbia to the starboard tack. The uncertainty of the wind was shown by the wide divergence of the courses of the two yachts as they went off on opposite tacks. They were heading about ten points apart. Shamrock seemed again to be having the worst of the struggle and to be losing ground.

But just for once the breeze did a kindness for the challenger. At 2:20 a slant drove in from half a point further west. This let the challenger up just that much while it headed Columbia off. Her headsails fell shaking and her way was deadened.  Capt. Barr had to throw her away off to get her going again, and when he had her under full way he put her on the port tack at 2:21:30. She was now a quarter of a mile to windward and half a mile astern.

Capt. Barr had to throw her away off to get her going again, and when he had her under full way he put her on the port tack at 2:21:30. She was now a quarter of a mile to windward and half a mile astern.

Again the wind took a hand in the contest, and Columbia caught a fine fresh puff which sends her bowling along with a big bone in her teeth. Sycamore did not like the appearance of things at this juncture, and thought it well to get into the hunt so he put Shamrock on the starboard tack at 2:22:20 and stood over toward the flying Columbia. Doubtless if Shamrock could now have crossed Columbia’s bow she would have done so, but Capt. Sycamore soon saw that it was not to be done, and at 2:25 he put his charge on the port tack. Shamrock was now about a quarter of a mile ahead, but a considerable distance to leeward of Columbia. The challenger had lost nearly all of her head by not sticking to the defender.

At 2:25:25 Columbia went on the starboard tack, and was once more heading toward the beach, which, however, was a long way off. Shamrock held her port board, Capt. Sycamore still thinking that her best footing was done on this reach.  At 2:27:45 Columbia went on the port tack half a mile to windward of Shamrock, but not on even terms with her. Barr was working short tacks at this juncture, feeling the wind with great delicacy, and skill. At 2:30:30 he put Columbia on the starboard tack again. Thirty seconds later Shamrock took the starboard tack. She was now holding a course half a mile to windward, but she was astern of Columbia.

At 2:27:45 Columbia went on the port tack half a mile to windward of Shamrock, but not on even terms with her. Barr was working short tacks at this juncture, feeling the wind with great delicacy, and skill. At 2:30:30 he put Columbia on the starboard tack again. Thirty seconds later Shamrock took the starboard tack. She was now holding a course half a mile to windward, but she was astern of Columbia.

The lightship wits in sight and a little figuring showed that Shamrock was somewhat nearer to it than Columbia. If the wind had backed more to the westward the challenger would have occupied a commanding position, for she would have been able to point right toward the finish. But the wind was not going to be so kind as all that, and the two continued as they were. Here again the smart footing of Shamrock kept Capt. Barr guessing. At 2:37:35 he put Columbia on the port tack and stood toward Shamrock. Once again the vessels were coming together on opposite tacks, the challenger having the right of way. Four minutes sufficed to show which was the windward yacht, for at 2:41:30 Columbia had to go on the starboard tack, forced about by the challenger.

Columbia was now under Shamrock's lee, but she would not stay there. Barr ramped hem off to give her speed, and as she rushed out of her uncomfortable position she backwinded Shamrock, and consequently Capt. Sycamore put his charge on the port tack at 2:45. Both yachts were now going very slowly, and they were beginning to feel the influence of the ebb tide, which was setting them off from the mark. At 2:47:30 Columbia went on the port tack to windward of Shamrock's course. At 2:53:10 she returned to the starboard tack, Barr evidently deeming it bad policy to stand too far out to sea. Shamrock followed suit fifteen seconds later. The wind was still lighter, and both were going at a snail's pace compared to the speed of the earlier tacks of the windward work.

Columbia was now under Shamrock's lee, but she would not stay there. Barr ramped hem off to give her speed, and as she rushed out of her uncomfortable position she backwinded Shamrock, and consequently Capt. Sycamore put his charge on the port tack at 2:45. Both yachts were now going very slowly, and they were beginning to feel the influence of the ebb tide, which was setting them off from the mark. At 2:47:30 Columbia went on the port tack to windward of Shamrock's course. At 2:53:10 she returned to the starboard tack, Barr evidently deeming it bad policy to stand too far out to sea. Shamrock followed suit fifteen seconds later. The wind was still lighter, and both were going at a snail's pace compared to the speed of the earlier tacks of the windward work.

As Shamrock headed away on this new starboard tack she was headed off a point and went right into a soft spot, while Columbia was going beautifully. Shamrock lost at least three lengths by this. At 2:56:50 Columbia went on the port tack and Shamrock followed five seconds later. Columbia's position had been much improved by the last tack. The wind kept coming in more westerly puffs, and each of these helped Columbia, as she was the more westerly vessel. At 3:10 they were three and a half miles from the lightship, and Columbia was one-third of a mile astern and to windward. She was footing much faster than Shamrock, because she was carrying a much better wind. Shamrock was sailing well, but was standing up too straight. At 3:13 Columbia dropped her slant and Shamrock got one which enabled her to head half a point higher than before.

At 3:16:25 Shamrock went on the starboard tack. The wind headed her a little and then Sycamore pinched her. Shamrock thus quite lost her way. As the yachts came together both pinched, and at 3:20:15 Columbia went on the starboard tack. Now the wind headed them, backing to westward. This was advantageous to Columbia, but Shamrock went on the port tack first at 3:20:40, Columbia followed at 3:21:30. Shamrock, however, succeeded in drawing ahead by smart footing. But Columbia was able to point three points higher by a favorable slant. Shamrock was now running directly away from the mark, and Columbia was winning.

At 3:16:25 Shamrock went on the starboard tack. The wind headed her a little and then Sycamore pinched her. Shamrock thus quite lost her way. As the yachts came together both pinched, and at 3:20:15 Columbia went on the starboard tack. Now the wind headed them, backing to westward. This was advantageous to Columbia, but Shamrock went on the port tack first at 3:20:40, Columbia followed at 3:21:30. Shamrock, however, succeeded in drawing ahead by smart footing. But Columbia was able to point three points higher by a favorable slant. Shamrock was now running directly away from the mark, and Columbia was winning.

But Shamrock was not yet out of the race. She picked up a little better breeze and in spite of the fact that Columbia was still doing nobly, saved herself from decisive defeat. At 3:29:25 the challenger went on the starboard tack, and once more had the right of way. The yachts were now pointing right into the excursion fleet, and while there was some little scurrying to widen the space for the contestants, the sea was one vast space of silence as everyone watched the last scene in the grandest of all yachting dramas. The lightship was close aboard of the racers, and the finish was only a matter of three or four minutes. Columbia was on the port tack and Shamrock on the starboard. The challenger was drawing toward the defender, and if she was on her bow would force her about. The experts strained their eyes and craned their necks and the inexpert guessed as hard as they could. At 3:30 exactly Columbia was seen to luff. Her headsails shook and she had to go about. She had been forced to tack by Shamrock's inalienable rights under the rules of the road.

Now both were on the starboard tack. Columbia under Shamrock’s lee, and both arriving to pinch so as to make the line, which was at an acute angle with their course.

It was only a moment before Capt. Barr saw that Columbia would not weather the committee boat, lying on the leeward end of the line, and so he ramped his yacht off to give her speed. She rushed out from under Shamrock's lee, and the minute she was clear Barr threw her to the port tack, at 3:35, and with the way of this on he carried her across the line. Shamrock was still rushing at the line, but Capt. Sycamore saw that she would go all the way along its front and hit the committee boat, so he also threw his yacht to the port tack, but she was in such a position that as she came about she headed directly at the lightship, and so he gave her a pilot's luff, or half board, as it is called, sending her across the line with her sails shaking and her head up in the wind. The finish was the closest ever seen, and the enthusiasm of the fleet over the victory was most intense.

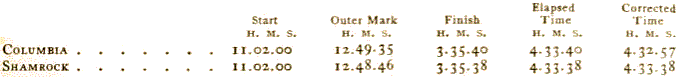

The summary : On the run to leeward Columbia occupied 1 hour 47 minutes and 35 seconds, and shamrock 1 hour 46 minutes and 46 seconds. Shamrock’s gain 49 seconds. On the beat to windward Columbia occupied 2 hours 46 minutes and 5 seconds, and Shamrock 2 hours 46 minutes and 52 seconds. Columbia's gain 47 seconds. On elapsed time, Shamrock beat Columbia 2 seconds over the course, but Columbia won by 41 seconds by reason of her time allowance of 43 seconds. |

I would have liked to win one race as a kind of consolation and relief. It is a hard thing to see your boat after racing nearly forty miles of water beaten at the last by a few beats of a pulse. This has been a very severe strain. I won't deny it. I felt it because I have worked so hard to win. While my disappointment was great, my joy would have been proportionately greater had I won this one race. While I am sorry I am on the wrong side, I'm glad the victory has gone to such worthy men as my opponents. They have won the battle in a most honorable way. The win today was the same as always— fair and square and honorable. I have nothing to protest, even if I wanted to protest. They have the better boat, but sometimes to win even with the better boat requires a wee bit of luck.