Yves GARY Affichages : 1199

Catégorie : 1920 : DEFI N°13

Le retour à des yachts de dimensions modérées et plus marins

Le retour à des yachts de dimensions modérées et plus marins© 1913 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, INC : August 9, 1913 - THE New York Yacht Club has recently announced that the Royal Ulster Yacht Club has signed the conditions for a match for the "America's" cup, and that the first race will be sailed Thursday, September 10th, 1914, the second, September 12th; ...

... the third, September 14th; other races which may prove to be necessary to be sailed on each following Thursday, Saturday and Tuesday. Thus this famous trophy, the best known and most valued yachting prize in the history of this great sport, after remaining for eleven years in the undisturbed possession of the New York Yacht Club, is again to be made the object of a memorable contest.

During the past three decades there have been eight series of races for the "America's" cup, all of which have been won by the defending yacht. The races were as follows: Genesta-Puritan, 1885; Galatea-Mayflower, 1886; Thistle-Volunteer, 1887; Valkyrie II-Vigilant, 1893; Valkyrie III-Defender, 1895; Shamrock I-Columbia, 1899; Shamrock II-Columbia, 1901; Shamrock III -Reliance, 1903.

In these races the time allowance which the larger yachts gave to the smaller was determined on the basis of their waterline length and sail area. Each designer was restricted to a waterline length not to exceed 90 feet. So long as he kept within this length, he was at liberty to make his yacht as broad and as deep as he pleased, and spread above her hull as great an area of canvas as he thought fit.

During these thirty years of competition, the operation of this rule produced a very extreme type of boat, with great beam and length on deck, of extreme draught, and carrying an enormous sail spread, requiring a very large crew for its handling. The effort to carry the largest possible sail spread showed itself both in the form of the hull and the materials for construction of both hull and spars. The extreme form of yacht produced is well illustrated by the "Reliance," which, on a waterline length of 89 feet 8 inches, had an overall length on deck of about 145 feet, a beam of 27 feet, and a draught of about 20 feet. In cross-section, the hull presented the appearance of a shallow champagne glass; the hull being shallow, with a flat floor and hard bilges. The hard bilges were carried well out into the bow and stern sections, with the result that when the vessel heeled, she immersed a longer waterline, the original 90 feet being extended to fully 105 feet at a heel of 20 degrees. The use of special steel for the framing and thin Tobin-bronze sheets for the plating enabled the designer to reduce the hull weights and proportionately increase the mass of lead at the bottom of the keel. A further increase of the lead ballast was made possible by the substitution of hollow steel masts and spars for those of solid wood. Such construction enabled Herreshoff to place about 95 tons of lead in the keel of the "Reliance" and to spread above her hull the enormous area of 16,247 square feet of canvas.

Now such a ship as the "Reliance" not only costs about $150,000 to build, but her running expenses are proportionately heavy. She requires a crew of fifty or more men effectively to handle her; she is an uncomfortable boat in a seaway; and after a series of races is over, she is useless for ordinary cruising. The fate of a yacht of this character is usually that she is broken up and sold for the value of her metal.

During the past few years American yacht clubs have adopted a new rule of measurement, which has produced a type of yacht that is practically as fast as the older type, and which has the advantage that her hull is deeper, more commodious and better suited for cruising. The old rule of waterline length and sail area produced a boat of very small displacement in comparison to the great spread of sail-a most undesirable combination. The new rule favors displacement and produces a boat with a deeper and fuller underwater body, and sharp ends, as against the full overhanging ends of the older type.

The contending yachts built for the last four series of races have been of approximately 90-foot waterline length, and in the preceding four series of races the waterline length was about 85 feet. Now before the length-and-sail-area rule had got in its pernicious work of producing freakish boats of enormous sail area, a boat of 85 to 90 feet waterline carried a sail spread of from 9,000 to 11,000 square feet, and such boats were reasonable in price and in cost of management, and were readily handled. When the exaggerated dimensions of the "Reliance" were reached, the cost and trouble of building and managing these yachts became very serious indeed. A return to yachts of smaller dimensions, such as contended for the cup in the seventies and sixties, became desirable. The British challenge sent by Sir Thomas Lipton through the Royal Ulster Yacht Club gave the length of the challenging yacht as 75 feet.

Now a 75-foot modern yacht carries a sail area approximately equal to that of the 85 to 90-foot yacht of 20 years before; and she is sufficiently large to provide a thorough test alike of the skill of the designer, the builder, and the competing skippers and crews. At the same time the cost of construction is cut in half, and so is the cost of operation. Moreover, under the new rule a yacht is built which after the races are over can be cross-bulk-headed and turned into a fast and thoroughly serviceable cruiser.

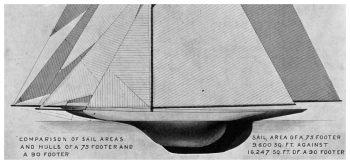

The accompanying superposed drawing of a typical modern 75" foot racing yacht and of the "Reliance" shows at a glance what an all-round reduction in size and increase in handiness is secured by a reduction of 15 feet in the waterline length. As compared with the "Reliance," the over-all length on deck is reduced from about 145 to 105 feet, the beam from 27 to 20 feet, the draught from 20 feet to 13 feet 9 inches, and the amount of costly lead that must be molded into the keel to give stability is reduced from 95 to about 37 tons. The main boom Is reduced from 115 feet to 84 feet and the height from boom to topmast drops from 155 feet to 111 feet. The cost falls from $150,000 to $80,000, and the cost of running the two types is as two to one. As to the prospects of our retaining the cup in this country, it must be admitted that the reduction in the size of the competing yachts is rather favorable to the challenger. In the first place, for the past decade racing among the large single-stickers has been confined in Great Britain mainly to yachts of from 60 to 70 feet waterline length; and, in the second place, Nicholson, who is at work on the challenger, is one of the younger designers who has shown originality and skill, his later yachts having made a pretty clean sweep in the regattas of the last two years. As far as can be learned, no positive steps have as yet been taken to build a defending yacht in this country.